Interpreting Ceramics | issue 14 | 2012 Conference Papers & Article |

|

||||||||||||||

Order and Disorder:Some Relationships between Ceramics, Sculpture and Museum Taxonomies

Michael Tooby |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Key words: ceramic installation; museums; taxonomies; artists’ projects. Introduction Debate about the usefulness or discomfiture of taxonomies of collecting and displays in Museums has become familiar. The discourse of how artists provide fresh insights into Museum collections through intervention and interpretation is also becoming well established. Less well considered is why Museums might work with artists, and how the very taxonomies with which Museums work can become fruitful terrain for understanding and engagement. Indeed, it may be time to affirm that the practice of inviting artists to make new work and redisplay collections in the context of subject or medium led categorization now operates as an integral component of museum curatorial practice. To illustrate, this text takes a series of acquisitions and projects made by Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. The examples all involve items which are ceramic, and all are made relatively recently. A discussion of the deeper timescale of acquisitions offered by a huge cross-disciplinary Museum such as this will only be touched upon, but the examples I will use illustrate some relationships to historic taxonomies and objects which it is to be hoped will continue to be discussed. The taxonomical category used to create the list of artists cited is ‘all making or using objects made from clay’. All are named authors, and despite regional and national distinctions evident in their work, come from a broadly European/North American background. The list therefore excludes ceramic objects made by factories or un-named vernacular makers. After describing these works and projects, some personal thoughts are offered on the means of analysis of taxonomies when considering different disciplines and shared concerns. Artists’ interventions and taxonomies of collecting at Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesIn a typically Mendelian hierarchy, the National Museum logs its acquisitions first within the Museum, then within departments, and below that within collecting areas. The examples used here come from three collecting areas in two departments. In chronological terms, we begin around 2004. Edmund De Waal was by no means the first artist to address the National Museum, its collection and its galleries. His involvement came at a moment when galleries across the National Museum and at St Fagans National History Museum were at the early stages of radical overhaul. Artists and creative practices were involved in these from the outset, whether as consultees about policy, creators of settings, as leaders of interpretation, or as makers of fresh displays and exhibits.1 He was, however, the first to explicitly address ceramics and taxonomy. He was encouraged to do so since the Museum’s teams had learned that artists in the role of, as we termed them, ‘Go Betweens’,2 offered the curatorial and learning teams rich ways to generate new insights and engage audiences, either directly or indirectly. Arcanum was a long-term project in which De Waal collaborated with the Museum’s curatorial team in studying the Museum’s ceramics collections and methods of display. One discovery was that the original donor of the greater part of the National Museum’s extraordinary historic ceramic collection, Wilfred de Winton, used a wonderful personal system of his own. In going back to de Winton’s original index, De Waal found headings such as ‘predominantly white’, ‘gold edges’ or ‘no flowers’ alongside date or place of making. In a natural dialectic, De Waal made new work whilst debating with the curatorial team the Museum’s overarching approach to the displays of ceramic objects, historic and contemporary. His project flowed into different streams. A major new solo exhibition juxtaposed a body of new pieces with his selections from the collections. The installation used storage and file cabinets as an entrance and spatial crossing. Over the project, debates, staged ‘in public’ and behind the scenes, discussed how to display the ceramics collections. Other work was made for long-term display in the collections beyond the closure of the initial show.

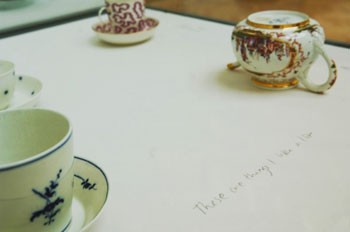

One of the recurring motifs in De Waal’s advocacy of a diversified display practice was the successive labelings given by successive owners to the items in de Winton’s collection. Displaying pots upside down enables us to follow the same journey, celebrating the different identities that the objects have enjoyed in each generation of use and appreciation. In his installation, De Waal used handwritten ‘labels’ such as ‘These are things I like a lot’ or ‘These are things I think children will like’ to build a sense of sharing personal response as a valid level of interpretation. Wider discussions of Museum acquisitions strategy happened around the same time. A policy of engaging the historic with the contemporary, the Welsh and the international, as points on a matrix of ideas and narratives, was developed and adopted by the Museum between 2002 and 2005. To illustrate, the acquisition strategy in art and applied art set to survey the Welsh and the contemporary, such as through acquisition of works by young emerging Wales based artists, like Claire Curneen, or leading artists with direct Welsh connections, such as Richard Deacon, and integrated this with the continuing formation of a canon of contemporary practice, building on identifying omissions where the collection was strong but was missing key figures , such as contemporary practitioners like Betty Woodman, or historical ‘gaps’ such as Pablo Picasso. A major work in ceramic by Richard Deacon, Empirical Jungle of 2003, was acquired in 2004, two years before Deacon was selected to be one of the artists representing Wales at the 2007 Venice Biennale.

Arriving as it did at the same time as the review of displays, this large-scale work took a place, literally and metaphorically, in the zone of the building devoted to the vitrine based display of ceramics. It was part of a series of acquisitions that would contribute further to the dialogue between ceramics and sculpture. In the Museum catalogue, it is sculpture, in the art collection. Claire Curneen was known to the Museum as a key member of the Fireworks ceramics studios in Cardiff, where she had graduated from the ceramics department at UWIC. Two strong and characteristic pieces have been acquired for the collection, one from the Blue Series (2002) and In the Tradition of Smiling Angels (2007) in 2002 and 2009 respectively. Both are beautiful figures, which reference late Mediaeval and early Renaissance painting. Both are in the applied art collection.

The Picasso ceramics were acquired as part of an important initiative known as the Centenary Fund. This was a collaboration between the National Museum and its great source of support for acquisitions, the Derek Williams Trust. Its purpose was to support major new acquisitions of works by significant artists not yet represented in the collections. The Museum acquired a group of ceramics and a painting. They are all art.

The work by Betty Woodman that was acquired for the Museum was Diptych: The Balcony. It is clearly from the tradition of American sculptural ceramic, and aside from its great physical presence, uses imagery drawn from the mainstream of classic modern painting and decorated objects. It can be seen from different facets, generating – if shown in a situation which permits - a sculptural sense of movement of the spectator around the work. It is applied art.

At this time, at St Fagans, the Museum’s social history curators were looking for ways to illustrate the new contemporary language in the arts that Wales has found for itself since devolution. Displays at the experimental Oriel 1 (Gallery 1) tested new ways of representing Wales to visitors from within and outside the country. One display motif was the new Welsh dresser, a centerpiece of the gallery.3

A recent work by Lowri Davies, a ceramic group which itself referenced the Welsh dresser, Hiraethu am yr Henebion / Longing for the Old and the Traditional, was acquired in order to be a long term feature of the display. It jostled for attention with a plethora of items, many ceramics, mostly production items, in a pastiche of the typical mélange of the domestic display. This was social history, then. Now, five years on, the art department has acquired a major new group of Davies’ work, Casgliad Nantgarw / My Nantgarw Collection. Its decoration references the historic Natngarw pottery, a few miles from St Fagans. It is in the applied art collection. This group is therefore available should different examples of Davies’ referencing of Welsh domestic life be required for the social history context, but adds to the recent canon of Welsh art where the importance of content to do with identity and history is prevalent in many artists’ practices.

Also in the opening displays of Oriel 1 at St Fagans in 2007 were a group of temporary projects by artists, selected to demonstrate the potential of a re-address of the social history, applied art and art collections. All were already using the idea of stereotype and caricature in Welsh identity, and had looked at the National Museum’s collections as a resource in doing so. Some had been included in a major show the National Museum created through its partnership scheme. One of the first projects in this programme was Dwyn I’r Goleuni / Brought to Light at Oriel Mostyn, Llandudno in North Wales.4 Some of the key works in the show were returned to the National Museum in the form of revised installations at St Fagans. We therefore saw the work of Marc Rees, who comes to installation from a dance and performance background, alongside artists such as Peter Finnemore and Bedwyr Williams. They all addressed the question of stereotype in identity, but Rees called upon the taxonomy of collecting as a narrative device. In Cabinet, Rees chose to address his Swansea Valley upbringing by integrating his mother’s kitchen furniture with a display of glass and ceramics culled from the Museum’s social history and applied art collections. He juxtaposed Museum objects and domestic furniture of his own family to generate a metaphor for his own journey to public recognition. The Swansea Pottery set on the table is therefore applied art, lent by the art department to the social history curators for an art installation in a social history space.

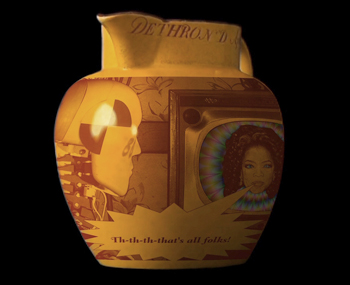

Artist. Object. Project. in 2009 was, like Brought to Light, another to involve artists working with the national collection in sharing chosen items with a small museum venue. Three artists, Catherine Bertola, Michael Cousin and Dierdre Nelson, were chosen from open submission. All responded to the historic ceramics collections in making new work then shown at Brecknock Museum, Brecon. Whilst Bertola and Nelson re-appraised production and vernacular pots through re-display and making new objects, Cousin integrated the motif of the vernacular occasional ceramic into his lens-based digital practice. His two works transposed decoration with contemporary political imagery using image transfer techniques. Plat du Jour was an object, and H1N1 a time-based work in video.

David Cushway takes fragility as his subject, in work across different disciplines of making but rooted in his making or deployment of ceramic objects. He thereby embraces the taxonomy of collecting and display as a secondary subject. His work Fragments (2006-7) was acquired as art, a video installation, another representation of emerging Welsh artist.

It was installed in the context of the historic ceramics gallery. A kind of reversal of Rees’ address of the same material, it puts the artist’s idea of the ceramic tradition within the original display, rather than displacing the display items into a new context. To summarize, we might characterize these examples by saying they show how the National Museum has diversified its interpretation, display and collecting strategies, creating opportunities to open new avenues of meaning and interaction. In so doing it has retained its taxonomies of collecting, leaving the questions of definition specific but with different methods of foregrounding their existence and questioning their nature and meaning. The Utility of Taxonomy – An Evolving Context for Museums The artist’s intervention as a genre has paralleled the changing role of the Museum, and the changing role of the curator. The Museum, originally a means to create and order knowledge, has become a public place, a resource deployed to allow variously skilled experts to participate with many different protagonists to set out a vision of the world. As the Museum has become increasingly identified as a civic resource, from which and in which a variety of experiences may be generated, the curator is equally cognisant of shifting meanings, transitory contexts and the need to constantly renew the appeal of the Museum. Aligning display and interpretation to the insights offered by artist has become a powerful tool at the curator’s disposal. The artist engaged in a practice of opening and questioning boundaries and using layered resonance and meaning must seek curators prepared to act as collaborators. I would speculate that many curators of my generation, educated in the late 1970s, their early career in the 1980s, came across the issue of the co-existent fragility of authoritative discourse and the dissolving of secure taxonomies of practice through some common sources. These included writing on sculpture, conceptual art and what later became known as ‘the expanded field’, and an anxious discourse around the status of the term ‘craft’. We followed or participated in civic and identity politics, debating the supposed duality of ‘art’ and ‘community art’. Much of the theory reflected the dominance of structuralism, semiotics and, later, post-structuralism. These arenas all suggested a crisis of history and authority, clearly expressed in the isolated and hierarchic nature of institutional practice in the arts and museums. To remind ourselves of this reference point, in a context generated by the display of sculpture, one can cite Foucault, as quoted by Rosalind Krauss, in her essay in response to a Rodin exhibition in Washington DC in 1981 :

Krauss continued, embracing museum display (as exemplified in the Rodin exhibition) as a field of practice, and using italics for the indefinite article just as Foucault does:

In an essay in the recent catalogue for the Royal Academy’s Modern British Sculpture exhibition, Jon Thompson describes what he terms a ‘middle generation’ of British sculptors in the 1980s. He suggests we can now see them as being between Caro’s St Martins and Hirst’s Goldsmiths contemporaries – Tony Cragg, and Alison Wilding are examples, as is Richard Deacon. Thompson suggests that they struggled – often fruitfully - with the question of making objects even while they were aware of the dissolution of taxonomies of fields of making and relativist interpretation. The artists tried to deal with the contradictory nature of fragmentation of meaning with the need to reconstitute the object with an evident ‘hand’, characterized by Thompson as being an attempt to re-craft sculpture. This is not the rejection of moulding, carving and ‘truth to materials’ by the makers of ‘New Generation’ sculpture in the 1960s, and not the playing with found objects, standard manufacture and strategies of foregrounding intervention and narrative which took over in the 90s. Instead it is a kind of middle way of dealing with the traditional concerns of sculpture through making self-contained objects which were yet operating in the expanded field.

Terminology in interpretation renewed itself as a critical issue in this ‘middle generation’. Referring to Richard Deacon’s work in wood and ceramic shown at Tate St Ives, fabricated at the same time as Deacon’s work in the National Museum, Clarrie Wallis points out the precision of Deacon’s choice of material, even while we search for an effective overarching descriptor for Deacon’s practice:

One crucial element of the practice of the ‘third generation’ of artists in Thompson’s genealogy, that which followed Deacon and his contemporaries, has been its embrace of taxonomy, and at the same time, the theatre of display – such as retail units, storage cabinets and the like - as subject. This developed alongside the use of locations alternative to the museum as sites for production and exhibition. These sites included disused warehouses, empty shops, churches and parks. Crucially, they also included places which interested artists by virtue of the potential differentiated routes to audiences, and access to collections of artefacts that reflected a much broader frame of reference than the modernist certainties presented in the white box spaces that so many were questioning. Social history and natural history collections in small and regional museums, for example, became powerful generators of new work and rich sites for engaging audiences used to using such locations but less familiar with contemporary visual arts. So too did stately or period homes open to the public. In the UK, residency based funding schemes helped push this practice into the foreground alongside studio-based work. This has created a hybrid within the more generally recognized arena of ‘relational’ or ‘participative’ practice. Artists have grasped the nuanced and challenging readings of objects where the diversity and scale of the collection setting – the country house room as tableau, the rich miscellany of the town social history collection – where the visitor was probably already thinking – what on earth is that thing in the corner? And, of course – didn’t your Grandmother have one of those?9 By the late 1990s / early 2000s, converging trajectories might be said to have intersected. On one track is the curatorial need to understand the impact of shifting practices in organizing museums and presenting displays, and how this plays its part in breaking down monolithic ideas about the relationships of knowledge and ‘access’. On another are the shifting practices that the artists, the makers, saw as the potential of a fragmenting field of practices.10 It is important to note that over the last ten years or so, ceramics has become a particularly powerful field for testing the relationship between object and expanded field of action. Two avenues are particularly evident. On one hand is a discourse about clay itself as medium; and on the other hand are ceramic products as they are understood in social and cultural terms. To take one example, in contrast to his writing elsewhere about collecting and display, Edmund De Waal explores Richard Deacon’s ceramic work not within a language which displaces the terminologies of studio pottery, but in recasting some the primal exegisis of that tradition but relocating it to the history of sculpture. He focuses on the primal appeal of clay itself, with an emotional investment which flows from his own experience;

This is a different order of discussion to, for example, De Waal’s celebration of the collecting of porcelain, his asking us to share the love and care invested in objects by past and present owners, and how we transpose such affection to objects in our own lives. Instead, he responds to Deacon’s work in a language of materiality, of feel, touch, dissolution and fixity. By the time the National Museum’s new galleries were being devised, then, the two arcs of curatorial practice and artistic practice intersected. Struggling to locate objects which were made in this medium which, apparently, has little value in the hierarchy of materials, artists and curators meet at a place which is not only framed by terms such as ‘a gallery’, ‘a wall’ ‘a plinth’ or ‘a display case’ and ‘a label’. These spaces, furnishings and apparatuses have also become the tools which many artists are now using as medium in order to explore the entwined meaning of the medium of clay and the medium of the museum. Taxonomy – A Shared Concern When submitting the abstract for this text, the intention was to suggest that the idea of multiple identity might be deployed to understand this situation. The literature of identity politics, particularly as explored in fields such as discrimination and exclusion, highlights the need, to understand shifting identity, through embracing multiple identity. The field of multiple identity does indeed throw up some valuable insights for the journey ceramic objects make from production and emission via mediation to collective understanding. The single label of an apparently uppermost, identifiable feature, suggestive of origin, is actually a repressive tool. No single being, no single object, possesses one single identity. Instead, identity is best expressed as a complex interaction of different elements, which may shift and become more or less important in a normal and nuanced existence. The way single labels – such as those given by taxonomies - persist despite being shifted and questioned is exemplified in the idea of ‘sticky signs’.12 This is the designation of key features of a group when they become signs that ‘stick’, to become persistent labels of individuals even when identity is complex, when the group has evolved or the individual is no longer part of that. Once a potter, always a potter. Once a pot, always a pot. Such signs of identity can also be reclaimed, of course, as in the best known example, the retrieval of an insult to become a label worn with pride. Though the seriousness of fields such as racism, ‘queer politics’ or the media labeling of minorities is perhaps an inappropriate comparison with our field, nevertheless we might reflect on our own day-to-day use of labels, like whether an artist chooses to reference themselves as a ‘ceramicist’ or a ‘sculptor’. Whilst revisiting the literature of multiple identity, however, I was reminded of the continuing power and relevance of the key structuralist analysis that underpins some of it. This literature is that to which I have already referred as the immersive reading for many of us in the 1970s. In particular, I am reminded of the value of the study of liminality. To summarise, this builds from a commonplace observation in the methodology of anthropology and language: that the world is inchoate, and to understand it, we adopt a process of naming. This happens at the level of functional interaction with objects and at the level of symbolizing the universe in which those objects live. In this process, which operates spatially and over time, some things cannot easily be labeled. This may be due to temporal change, or to the possibility of being outside simple categories. The classic examples of the first are rites of passage - weddings, funerals - when individuals and their community need to recognize that people’s states have changed. The classic examples of the second are objects and processes that cannot simply be placed in a category by causal explanation, particularly when they may regularly shift between states, or are found outside their normal location. The best known example of the application of this theory is Mary Douglas’ celebrated work ‘Purity and Danger’. This is a study of ritual cleanliness and its opposite, the symbolization of ‘dirt’. The best definition of dirt is that of ‘dirt as matter out of place… Shoes are not dirty in themselves, but it is dirty to place them on the dining table’.13 Ah, she anticipates you saying – but shoes might really be dirty so we avoid the potential danger of pollution with such sensible rules. What, then, about what we might call housekeeping – dirty kitchen things found in a bedroom, or clothes on a chair in the kitchen? In elaborating the symbolic and ritualized nature of the answers we may give to these questions, Douglas does not deny the usefulness of creating a schema of the world in order for us to understand it. On the contrary, she emphasises its importance. In a chaos of shifting impressions, each of us constructs a stable world in which objects have recognizable shapes, are located in depth, and have permanence. In perceiving we are building, taking some cues and rejecting others. The most acceptable cues are those which fit most easily into the pattern that is being built up. Ambiguous ones tend to be treated as if they harmonized with the rest of the pattern. Discordant ones tend to be rejected. If they are accepted, the structure of assumption has to be modified. As learning proceeds objects are named. Their names then affect the way they are perceived next time: once labeled they are more speedily slotted into pigeon holes in the future. From this two of her further general points can be noted. First, that in cultural and institutional forms, the generation of taxonomies tends to be conservative: Culture, in the sense of the public, standardized values of a community, mediates the experiences of individuals. It provides in advance some basic categories, a positive pattern in which ideas and values are tidily ordered. And above all, it has authority, since each is induced to assent because of the assent of others. But its public character makes its categories more rigid. A private person may revise his pattern of assumptions or not. It is a private matter. But cultural categories are public matters. I have spent a long time citing what is I assume to be a familiar analysis. But I am doing so partly because, in my re-reading, I am struck by the way Mary Douglas concludes this passage with a statement which acts as a challenge. Any given system of classification must give rise to anomalies, and any given culture must confront events which seem to defy its assumptions. It cannot ignore the anomalies which its scheme produces, except at risk of forfeiting confidence. This is why, I suggest, we find in any culture worthy of the name various provisions for dealing with ambiguous or anomalous events. Douglas briefly mentions that anthropologists other than herself have ascribed the role of the priest and the poet to those who find out, express and in some cases control these ambiguities and discordances. In seeing how the ordering of the world is disrupted by ambiguity, we find that the difficulties in labeling happen on the border, or in a transitional zone in time. Societies also create understood, intentional zones where ‘in-betweenness’ makes it possible to experience transition or anomaly. Victor Turner was one of Douglas’ contemporaries who pointed out that societies often deliberately create – or allow to continue – such zones of ambiguity and transition, to which the term ‘liminal’ applies. Priests and shamans live both within and outside society by exercising a role of control and access to the liminal. Their power lies in permitting or presiding over ceremonies in which rites of passage take place, or guarding special places which can be ambiguous spaces within which taboo experiences of power and re-ordering are negotiated. Turner states :

Turner used modern and Western analogies like monasteries and communes, festivals, and the stages of rites of passage such as honeymoons following weddings, to illustrate the role of liminal places and time zones. Inevitably, we think of the artist and curator as different versions of the priest and the shaman. In affording space to the artist to address taxonomy, the curator cedes power by allowing the established cultural codes of naming to be disrupted. Over time, if insights and experiences are consistent, these might even be assimilated into new institutional rules. The new orthodoxy itself requires challenge. The practice of ambiguity can itself be turned back on its own tradition. One version of the liminal outsider is the Fool, the trickster, who by satirizing and outwitting those in power points to a deeper truth or fundamental ambiguity of unaddressed meaning. Such figures are often apparently innocent. To conclude, therefore, I will offer two recent versions of the artist as outsider, creating fresh insights into the possibilities of breaking through structure. Here is Michael Cousin’s commentary on his Brecon project:

The multiple identity of the artist – as maker, seer, finder of gaps, shifter of objects between categories, resource of knowledge – can in its freedom offer new opportunities, new knowledge and new experiences to the curator and, most important, to the audience. This possibility has been seized by Cousin’s contemporary and colleague, David Cushway. Like Cousin, Cushway uses video; unlike Cousin, he uses it as part of a practice grounded in a ceramicist’s training. Two of his most recent works have involved staging performances in ceramics collections. One was made for the temporary closure of the Glynn Vivian Gallery in Swansea. In the course of it members of the Gallery’s audience share their thoughts about items as they are packed away. The other was made, at around the same time, in collaboration with Andrew Renton and the National Museum’s curatorial and conservation team. It is called ‘Tea at the Museum’ and shows Renton and Cushway as they remove an historic tea service from a display case in the Museum’s principal gallery of historic ceramics, and take tea, with evident pleasure.16

The old taxonomies do not remain to be dissolved, but stand as important tools for opening up new meanings, and helping to reconciling these against history and personal knowledge. Artists are invested with a special role and responsibility, as they posses the power to shift objects, practices and meaning into powerfully ambiguous ‘liminal spaces’. This power, even when expressed through different technical disciplines, is played out on the shared terrain of understanding materiality and how it operates in naming and understanding our world. The curator’s role is in understanding not the limitation but the potential of taxonomy. The curator must rise above operational issues that lie behind the tendency to make taxonomy a conservative device. Operational strategies such as collecting, conserving and labeling are support structures not ends in themselves, a position increasingly widely recognized in the curating community. Curators are asking more and more questions of their operational conditions. The challenge is how to make sure they can find something in the museum store, or locate it in display in a meaningful context, but also ensure that each nuance of discovery, each possible way of renaming it and giving it an open identity uses description to open doors for audiences and not close them. The opportunity to work with an artist often acts as permission to do so. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 1 This process began in 2001 at the National Museum, completed there in the galleries opened in 2011 and now being taken up in subsequent programmes; and continues at St Fagans, with a re-presented programme of contemporary (in the sense of practice) displays and projects beginning in 2006-7 and continuing into the coming years as ‘Making History’. The underpinning policy documents are ‘Views of the Future’, ‘The Future Display of Art’ and ‘A world class museum of learning’, which can be referenced via the Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum website. www.museumwales.ac.uk |

|||||||||||||||

Order and Disorder • Issue 14 |