Interpreting Ceramics | issue 15 | 2013 Conference Papers & Article |

|

||||||||||||

From Ceramics to the Bronze Age: Commercializing Sculpture in the United Kingdom and on the Continent – A JuxtapositionPart ll Isabel Hufschmidt |

|

||||||||||||

|

‘Invention of arts, with engines and handicraft instruments for their improvement, requires a chronology as far back as the eldest son of Adam, and has to this day afforded some new discovery in every age.’(Daniel Defoe, ‘The History of Projects’, in An Essay Upon Projects, 1697) Taste and Aesthetics vs. Art Married to Industry? When technical improvements and mechanization ‘take command’, to use Giedion's expression,1 is the originality of the art work and/or the artist himself threatened? Cheverton, perhaps slightly disquieted by the consequences of the employment of his sculpturing machine, declared in 1837, then seven years before he patented his apparatus:

In France we find the same reflections about the topic, perhaps even with more eagerness than in Britain in view of the stronger overshadowing force of the present commercialized industry of art and the modern art market, very premature by means of their incomparable acceleration in development and extension. (Fig.1)

Actually, there are four aspects which can be repeatedly found throughout several treatises about art and industry in various critical accounts, newspaper articles etc. of that time: questions about the claim of sculptural works as art works which have entered commercial production and distribution and have mainly been detached from the artist’s hand by then; doubts regarding their aesthetic and artistic quality; objections regarding their ability to educate public taste; thoughts about their final intention, respectively destination due to subject, scale as well as execution. An exemplary case which gives contour to these aspects and to the problem hinted at between the lines pronounced by Cheverton was to happen in France. Among all kind of court proceedings dealing with the exploitation and distribution of sculptural works at that epoch one particular case will be presented here as it gives a precise impression of the obstacles with which a publisher of sculpture had to cope with. It is a judicial case offering us insights into questions of plagiarism, property rights closely related to the reproduction of sculpture on an industrial scale by mechanical means, especially assisted by the application of the pantograph, and by consequence, the claim of such an object - gone through a technical process of creation - to be an art work. The famous fondeur-éditeur Fedinand Barbedienne had sued against surmouleurs for having illegally reproduced and distributed works, mainly reduced examples of ancient masterpieces, originating from his production. During this Procès Barbedienne, documented by Charles Blanc in a report published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1862, the crucial issue in terms of the success of the lawsuit was whether the objects created by the réducteur and then reproduced serially throughout a partly mechanized process were to be considered as art works. By consulting Blanc's report, passionately defending the publisher's side and the character of his production to be a true production of art works in their own rights, the reader learns that the case was dismissed. The original source will be cited exhaustively at the end of this text in order to provide an opportunity for closer comprehension of the case. It is given in its original tongue, showing its beautiful language of argument, and it is followed by an English translation by the author of the present essay (Appendix I). Before focussing on the British position in this controversy of the art industriel and to return to the subject's root of discussion, the contrasting attitudes held by prominent figures of the French debate such as Gustave Planche and Léon de Laborde are now presented and discussed. In his treatise ‘De l'union des arts et de l'industrie’ published 1856, Léon de Laborde extensively considers the theoretical support of the concordance between art and industry. Revoking first the common statements spread by the opponents, the author formulates the clear aim of this union being to the advantage of art, the artist and the public. He declares: Loin donc de tuer les arts en les repandant, cette large diffusion sera comme la cloche qui appelle à l'église le monde croyant. … la culture des arts sera étendue à tous.3… former le goût de cette aristocratie nouvelle qui s'appelle tout le monde.4 As we shall see later, he thus echoes certain convictions that Henry Cole had previously propagated for a decade or so. However Gustave Planche rejects this position and in direct response to the explanations laid down by De Laborde, the famous critic judges the naïve approach of the author to the alliance between art and industry by warning off pejoratively the true reality of their consequences (Appendix II). One may say De gustibus non est disputandum, but what Gustave Planche foreshadowed seemed to be a danger which, for the British side, Marion Harry Spielmann (1858-1948) was to summarise in a quasi-Socratic phrase about half a century later: ‘bad taste is worse than no taste at all; for “no taste” may be educated, but “bad taste” is vicious already’.5 In view of the hassle in France, Britain had witnessed, preceding by 20 years the case alleged here, the decisive impulse for its art industry in order to equal France, although with some slight delay. Those involved into the discourse were not less aware of the menace of corruption, thus it was the prevailing credo and goal, similarly to what had been propagated in France, that a commercialised art production, the union of art, handicraft and industry, was not meant to be the arts' failure and shall not be, in terms of protecting the new alliance against any recklessness of the industrialization's ambivalence, against its facile disposition in the abuse of its proper means and aims. Owing to a respected representative and relentless preparer of this movement like Henry Cole as well as the firm support by the noble class, the keen sponsorship of the Sutherlands, especially on the pottery's side, the royal family and the approval by leading artists, critics and press, the conviction of mutual benefit, the progress as well as promulgation of art via industry and the progress of industry by art's assistance, finally leading to the education and refinement of public taste, could take its shape. In short, as Cole would say, ‘an alliance between fine art and manufactures would promote public taste’.6 Years later, incidental kinship to this idea is awarded by Llewellyn Jewitt. In his famous historic treatise The Ceramic Art of Great Britain, published in two volumes, the author exclaims – in the chapter about Worcester - his position in a long and significant passage, promoting herein the central status of pottery manufactories and the responsible challenge these seem naturally to be charged with:

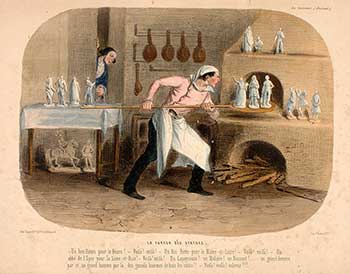

And it is at that point where Felix Summerly and the Society of Arts step in with their realization of this idea. The goal is precisely fixed in 1847 with a presentation entitled promisingly ‘ART-MANUFACTURES: COLLECTED BY FELIX SUMMERLY, Shewing the Union of FINE-ART with MANUFACTURE. (Fig.2) The introduction to this catalogue-like prospect summarizes the essentials of the enterprise, seeking confirmation by historic approval and emphasizing the enjoyment of co-operation with renowned contemporary artists and manufactories. And just like in a catalogue of those notorious French foundries, the range of objects extolled comprised sculptural works and decorative items as well as arrangements in various materials.

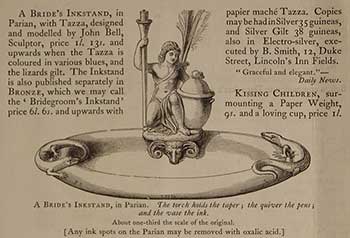

Very promising indeed, and one could have anticipated a long story of success, if we take in account the positive reactions which can be gathered from various journals and the vast publicity campaign Cole brought into action, but the entrepreneur abandoned the business in 1849 already, probably for several reasons. (Fig.3) One could have been the fact that the profits did not work out so well as conceived; another, potentially damaging in terms of public relations, might be seen in the attacks in the Art Union journal which, on the occasion of the annual exhibition of British Manufactures for the Society of Arts in 1848, organized by Cole, criticized the display of objects as it was mainly dominated by Summerly items.9 Moreover, anonymous letters published in the same journal criticised the scheme of agreement Cole required from the manufacturers who had all the financial risks on their side. Nevertheless, in 1849 Cole was already completely occupied with establishing the first Great Exhibition of All Nations. Compared to his previous enterprise, this meant the ultimate outcome of his visions to which the Art Manufactures had been a ‘mere’ preparatory challenge and experiment; preparatory, but inspiring, shoulder to shoulder with the Art Union’s efforts, drawing out the potential of sculpture introduced to a market system, to private consumption – and that in various facets.

From the examples given we can see that there are many sides to this story –probably too many to cite them all. Even if completely aware of the developments of the time, especially those in neighbouring countries, the British art industry seemed to miss its moment of opportunity. Just very late in the century we witness a stronger demand for a more independent commercialization of sculpture, independent in terms of direct co-operation between publishers, foundries and artists. Between the first attempts from the 1830s / 1840s and the outcomes at the end of the century we have a gap of uncertainty in proceeding, a stasis or even a kind of reticence. We come full circle with the introductory comment by Cheverton in 1837 and then further comments by Onslow Ford in 1889 and by the critic and president of the Art Workers Guild, George Simonds, in 1886, not an enthusiast of the urged popularization of sculpture via marketing ambitions. Both Ford and Simonds declare the predominant role and control of the artist in any execution of a design or work of art generated by his mind and hands, a control which should not end even, and especially when, his creations enter the channels of commercialization. Simonds is actually blaming

By referring to the particular example of designs in silversmithing, Onslow Ford expresses himself in the same direction, urging even more the artist’s accomplishment in the knowledge of techniques and handicraft:

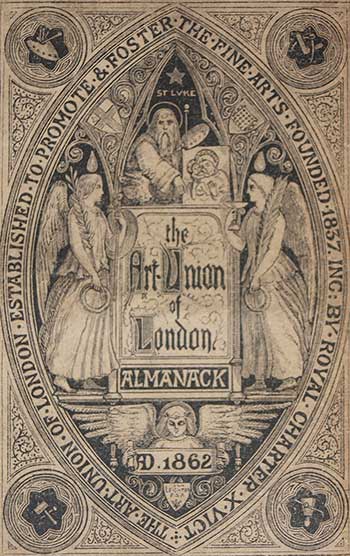

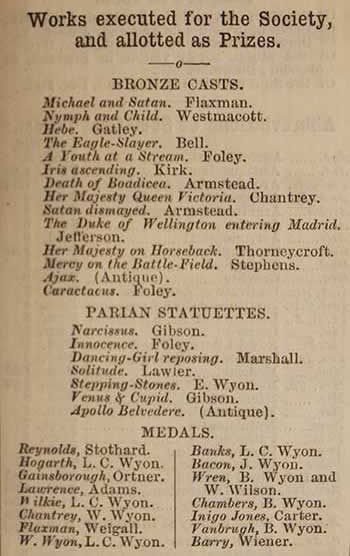

In order to take up these thoughts and coming back to the beginnings before going further, it was in the Journal of Design and Manufactures of 1849/1850 that we already find treated essences of the subject exposed until here via different perspectives and statements. Dedicated to the Duchess of Sutherland – the family notoriously connected to the progress of the Potteries – the journal neatly illuminates the manifold faces of artistic, manufacturing and trading developments as well as activities in interrelation. By browsing through the Miscellaneous section of the issue the reader comes across the ‘Letters on English Bronzes’, a crucial account not only in terms of the topic of this article, but in showing how overtly the changes and challenges were perceived at that time. The author of the ‘Letters’ - in the first part signing with “an observer”, in the second as a certain B.J. - , after having declared the superiority of the French bronzes by which the English ambition had been awakened, recalls a visit he paid to the firm of Eck & Durand in Paris. The writer puts emphasis on the skilful execution by the workers employed, their knowledge and comprehension of the artistic challenge, owed to the specialized education at the école commun. He then hints again at the progress which can be seen in the production of bronzes in England by referring expressly to the impulse the Art Union gave in this direction, although he is very clear about the need of improvement his country still has to face before being able to compete seriously with the works from abroad. But he sees at least one obstacle left behind, the separation of ‘ornament’ and ‘art’ which now ‘have no dividing line between them’, for him the condition of any improvement and progress in this field, a condition of which not only manufacturers, but the artists and the public are equally aware of, ‘which … is fortunately now obtaining credence in this country’.12 Turning Clay into Bronze – The Way to Publishing Sculpture The threshold between the tradition of figure making in ceramics and a true marketing of art, an industry of art in its proper sense, was the introduction and rapid elevation of Parian ware. Much has been written about the slightly misleading story about who invented this innovative and revolutionary paste.13 In fact, Parian meant the turning point for the commercialization and marketing of sculpture in Britain. Successfully introduced almost simultaneously in the 1840s by Copeland under the term statuary porcelain and by Minton which accorded the generally accepted name Parian, the new paste proved itself perfectly applicable to the production of statuary. The unglazed body was of particular hardness, and colour as well as texture and in its emulation of marble it was incomparable to any ceramic composition before. Wedgwood & Sons also joined the production of Parian calling it Carrara, referring alike to the precious material. Other important manufacturers dedicated themselves to the production of Parian and every firm seemed to have its own recipe of the body. Prominent amongst these firms were the Royal Worcester Porcelain Works, Robinson & Leadbeater at Hanley, successors of Giovanni Meli (active from 1858-1862) in 1865, Brown-Westhead, Moore & Co. (active 1862-1904), John Rose & Co. (later Coalport China), T. & R. Boote at Burslem, Robert Cooke of Hanley (active 1862—1879) or William Henry Goss Ltd. (active 1858-1929).14 The wave of Parian was impelled by the support of Summerly's Art Manufactures founded by the omnipotent and zealous Henry Cole as well as the Art Union movement born in the 1830s. (Fig.4/5) Last but not least, a shift in patronage and capital had taken place, as now a class of bourgeois citizens desired sculptural decoration and objects of contemplation for their home. Several firms like those named above, Summerly's Art Manufactures and the Art Unions could satisfy this desire, and the two latter additionally awarded commissions for sculptural works - scaled down or directly conceived in small dimension for reproduction - as well as artistically designed and decorated items with the clear aim to make art a democratically accessible part of public and private life. The very ground and starting point of this project was the promotion of an alliance between art and manufacture which was to result in the stable ‘anchorage’ of a commercially aligned production and distribution of sculpture, as a tight network of advertisement and retail, national as well as international, was installed, in turn enhanced by the International Exhibitions. Even if severely criticized regarding their business structure, especially the lottery system,15 and regarded with some suspicion in terms of their accelerated production and distribution of art works, seemingly without distinguished choice, but just in the interest to “collect” and keep subscribers, the Art Unions, spread all over Britain (with the exception of Wales).16 The Art Union of London17 and the Crystal Palace Art Union held the most prominent positions and were particularly pivotal in boosting the public interest in sculpture. Slightly before Parian emerged, the Art Union of London was already occupied with issuing statuettes in bronze by 1842.18 And at this point we have come full circle around the prevalent subject of published, marketed sculpture on British soil, not only in ceramics, but in metal, especially bronze. And the following words by Canova, slightly modified by Spielmann, seem to resound: ‘Clay is the Life; Plaster the Death; Marble and Bronze the Resurrection.’19

But a crucial prerequisite for the edition of small statuary is a ‘platform of production, marketing and distribution’, i.e. first and foremost - regarding in particular the serial reproduction of small bronzes - foundries specializing in cire perdue, the casting process whose development had until then been rather neglected in England, but which, in comparison, had been brought to a high standard of perfection in France since the 16th century. Indeed a history of the French art foundry, utilising the knowledge and continuing in the heritage of antiquity, can be traced back to the production of sculptures at Fontainebleau. An indication of the admiration towards imported French bronzes in Britain at a time when the serial production of sculptural works in this country was struggling to keep up developments across the channel, is given in this extract from the Building News in 1875:

In the second half of the 19th century, several foundries were established which often preferred to employ French craftsmen in order to implement the project of ‘English-born’ editions of small statuary. They sought to establish a form of ‘free enterprise’ industrial production and marketing of sculpture of a kind that had long been established in France. This can be seen with the involvement of firms such as Arthur Leslie Collie, Bellman & Ivey's, Thomas Agnew & Sons or Graham & Jackson (Fig. 6) In fact, the influence of French sculpture in Britain (see discussion in the first part of this study in Interpreting Ceramics, issue 14), was not only throughout teaching alone, but by the sheer presence, distribution and exhibition of the works via institutions such as the Royal Academy or Grosvenor Gallery; true ‘instances of consecration’, to use a term employed by Pierre Bourdieu.21 French imagery, aesthetic language, its poetry of subject and form, as also the tangible realization, the material execution, the art of founding, experiments with polychromy and the junction of different metals in one work, were more than an incentive to young British sculptors who not infrequently sought to expand their artistic horizons and accomplishment by travels to France. Amongst these were Percival Ball (1845-1900), Harry Bates (1850-1899), Goscombe John (1860-1952), Holme Cardwell (born ca. 1815, active 1836-1862),22 George Frampton (1860-1928) and Alfred Gilbert.

Searching for and developing a modified artistic language, poetically refined and spiritually distinguished, related to value, significance and expression of form and surface on one hand, the British sculpture scene, having inevitably to recognize on the other hand the French superiority regarding founding techniques and the special French spirit of commerce by the edition and partly international trade of sculpture, evolved a proper commercial ambition joined by the desire to keep up with workmanlike refinement and mastership in founding so as to implement ways of publishing and marketing sculpture on British soil. And some sculptors had long since noted, regrettably, the lack of both a platform for the serial production and the largescale distribution of sculptural works, notably Onslow Ford (1852-1901) who stated in 1888.

In his presidential address before the National Association for the Advancement of Arts and its Application to Industry he made himself quite clear in these terms. The following quote is thus crucial as it combines essential thoughts of popularizing and marketing sculpture seen in close relation to the situation of the sculptor at that time looking for financing himself independently from commissions; a first hand self-reflective insight by an artist of the artist’s position and capabilities – not least as entrepreneur. Even more intriguing, Ford emphasizes a peculiar development, the shift to the private and intimate art consumption as appropriate and comprehensible in terms of conditions and requirements of modern private life.

The premise for an industry comparable to that in France was based, however, to a significant part on the possibility of a professionally established win-win cooperation between artists and publishers as well as subsequently in an enhanced infrastructure of production and marketing. It is not the case that there were no foundries and dealers in Britain, but to expose an important aspect, the tradition of cire perdue-casting, brought to a masterful degree in France since centuries, had been underregarded and underdeveloped. Plaster figure makers and craftsmen employed for bronze casting came mostly from Italy and almost dominated this branch of production since the first half of the century. While in France the edition of small sculpture – comprising ceramics, bronze, plaster and other sorts of material – had achieved the status of an industrial branch in its own right with a vast expansion and economic stability, representing a stimulus for the art market comprising a machinery of marketing via advertisement, sales catalogues and sales points, the British art production struggled to keep up. From around the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, several foundries were established, namely Cox & Sons (Thames Ditton Foundry, fd. 1874), John Webb Singer (fd. 1852), Henry Young & Co. (fd. 1871), Moore, Fressange & Moore (active from 1848 until 1852), Rovini & Parlanti (fd. 1894) as well as Elkington, known for the electroplating process, but embarking on bronze founding, too, in the 1850's, or the firm of John Ayres Hatfield (1815—1881, bronzist from 1844, bronze manufacturer from 1851) or that of Enrico Cantoni (fd. 1889), and several of them often preferably relied on French craftsmen, just like British foundries in existence before.25 (fig. 7/8) Next to brass and iron casting, commonly in practice, lost wax casting had been successively brought back into existence by the efforts of Alfred Gilbert, experimenting along with Stirling Lee (1857-1916) with whom he set up a foundry in 1885,26 and Onslow Ford, as well as the know-how of the Italian-born caster Alessandro Parlanti and Thames Ditton Foundry.

Among those sculptors interested in editions of their works on a small scale like Hamo Thornycroft (The Mower, 1884; Teucer, 1882), Alfred Gilbert (Kiss of Victory, 1882; Perseus Arming, 1882), Frederick William Pomeroy (Perseus, 1898) or the Australian-born Edgar Bertram Mackennal (Circe, 1893), the two former established themselves as their own publishers – in the footsteps of French artist-founders like Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875), Pierre-Jules Mène and Baron Marocchetti or Sir Richard Westmacott and Sir Richard Chantrey (1781-1841), the prominent British examples, both with foundries in Pimlico, while Westmacott is said to have been 'the first caster of bronze in the Kingdom'.27 And Hamo Thornycroft, some generations after the latter, one of those who recognized and made use of the benefit of popularizing sculpture, was exemplarily praised in the Vanity Fair issue of February 20 in 1892 with the words 'he is the modeller of so many small bronzes that he is like to revive the Bronze Age; for his bronze statuary is becoming quite the thing'.The sculptor himself had already declared very frankly and insistently the need and important role of small sculpture in a lecture before the students of the Royal Academy in 1885:

But he comes even more acutely than ever to the point in a letter to his fiancée Agatha Cox on November 13, 1883:

Analogous to the edition of sculpture in Parian, the interest in the reproduction of small bronzes lay in the reduction of popular, successful sculptural works, for instance extracted from their context within a sculptural program of public monuments - like those allegorical figures from the Wellington Memorial by Alfred Stevens (1818-1875) - or they were directly conceived in small dimension for reproduction.30 Moreover, artists provided designs and miniature sculpture for decorative as well as arts-and-crafts objects, and this was not very different from the practice in the French art industry, but followed equally the long tradition of British ceramic works in the field of applied arts. To go further, on the plane of marketing, artists could entrust firms like that of Arthur Leslie Collie (1834-1905) with organizing the works' production and executing their marketing. Quite evident, the eager ambition towards the redirection of sculpture, especially on a commercial scale, and thus also exploring possibilities of genre aesthetics via the medium of small scale, experimenting with the choice of subjects, with form, style, effects of surface, expression, challenging thus the beholder's perception and attitude towards sculpture, was particularly conceived and lead by the artists of the New Sculpture. And the unanimously positive assessment by critics like Edmund Gosse (1849-1928)31 as well as Alfred Lys Baldry (1858-1939) reinforced its consolidation, just as the 'First Exhibition of Statuettes by Sculptors of To-Day, British and French' at the Fine Art Society in 1902, organized by Marion Harry Spielmann who also wrote the show catalogue’s introduction, 'Sculpture for the Home',32 made its very own contribution of public relation. In 1895 already, Gosse was keen in promoting the 'new' place of sculpture in daily life: I wish I could convert all my readers to an acknowledgement of the beauty of bronze. … in a work executed in bronze, we get very much nearer to the actual touch of the artist than in any other substance … By far the most adequate way … in which sculpture can be used in the house, is by the introduction of statuettes … Such bronzes d’art are highly appreciated in France, where they form a recognised branch of domestic ornamentation, and are, I understand, the chief source of income to many leading French sculptors. It is strange that they have hitherto achieved so little success with us. Mr. Collie, of 39B, Old Bond Street, who publishes charming specimens by such eminent sculptors as Leighton, Thornycroft, Onslow Ford and Frampton, deserves high commendation for the zeal with which he has sought to encourage this department of the art.33 (Fig.9)

And it was Spielmann, next to Gosse, who would additionally point out the contextual influence emanating from French sculpture in his unequalled account British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day from 1901:

Conclusion It seems to be very revealing for the comprehension of the intricate British situation, the eager want of competition with bronze productions from abroad on the same commercial scale and quality level, Collie's exemplary enterprise didn't survive for long. After an activity as a 'publisher of sculpture' of merely nine years (1888-1897), however in tight relation with the retailers Thomas Agnew & Sons at Old Bond Street and the foundry J.W. Singer & Co. of Frome, the business was given up.35 In fact, the British attempts to establish a competitive industry of bronze casting and publishing was brought forth when the boom of serially reproduced sculpture was already fading in France and the enthusiasm for Parian, too, diminished from about the 1870s onwards. Although weakened, the French production remained overshadowing to the efforts in England. To summarize: as French aesthetics had left their unerasable traces within British sculpture, the intensity of the very Franco-specific commercial spirit wasn't to come to the truly full blossom in England, to be taken over in its whole manifestation. Nevertheless, whilst trying to emulate the French example, the realization and implementation of a 'naturalized' commercialization of sculpture took its proper shape, sustained a form of its very own kind, tradition and history in Britain. It looks upon and owes its impulse to its very own track of evolution - admittendly again not completely free from any French interference, as it could be seen, but with a particular British mentality and character - i.e. by departing from the industrialization of an intitially purely artisanal métier: pottery. The preparation of the 'bronze age' has thus its roots by essential parts in the 'mechanization' of the hand's execution, the industrialization and commercialization of the work in clay; and to 'abuse' again, for the purpose of the last words, Canova's declaration, morphed and extended by Spielmann, which might be permissible for the emphasis of what has been expounded, we conclude: Clay is the Life, Bronze the Resurrection. ONE'S-SELF I sing, a simple separate person, Of physiology from top to toe I sing, Of Life immense in passion, pulse, and power, Top of the page | Download Word document | Next

1 Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command. A Contribution to Anonymous History, New York/London 1969. 2 cf. Ed Allington and Ben Dhaliwal, Reproduction in Sculpture: Dilution or Increase?, The Centre for the Study of Sculpture, The Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 1st January 1994, www.henry-moore.org/hmi-journal . 3 Léon de Laborde, 'De l'union des arts et de l'industrie. Rapport sur les beaux-arts et sur les industries qui se rattachent aux beaux-arts', 2 vol., Paris 1856, p. 46 (vol. 2). Translation: 'Far from killing the arts by distributing them, this large diffusion will be like the bell calling the faithful to church … the culture of the arts will be extended to all … forming the taste of this new aristocracy called everybody 4 De Laborde, 1856, (vol. 2), p. 49. 5 Marion Harry London 1901, p. 6. 6 Henry Cole, Fifty Years of Public Work, 1884, vol. I, p. 107, cf. Giedion, 1969, p. 348. 7 Llewellyn Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain. From Pre-historic Times Down to the Present Day, London 1878, vol. I, pp. 250-251. 8 Felix Summerly, Art-Manufactures. Collected by Felix Summerly, Shewing the Union of Fine-Art with Manufacture, 1847, pp.3-4. 9 Shirley Bury, 'Felix Summerly’s Art Manufactures' in Apollo, 85, Jan. 1967, pp. 28-33, pp.32-33. 10 George Simonds cited in Susan Beattie, The New Sculpture, New Haven, 1983, p.185. 11 Onslow Ford, 'Section of Sculpture. Presidential Address by E. Onslow Ford, A.R.A.', in: Transactions of the National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry, London 1889, pp.117-122, p.122 12 ‘Letters on English Bronzes, No. I’ / ‘Letters on English Bronzes, No. II’, in: Journal of Design and Manufacture, Miscellaneous, September, 1849 - February, 1850, pp. 150-152 / p. 184. 13 cf. ‘The controversy over who first originated the idea of Parian’, in: Robert Copeland, Parian. Copeland’s Statuary Porcelain, Suffolk, 2007, pp.23-37. 14 Paul Atterbury (ed.), The Parian Phenomenon: A Survey of Victorian Parian Porcelain Statuary & Busts, Somerset, 1989, see chapter 'Figures and Busts by Miscellaneous Makers', p.237 et seq. 15 An exemplary resume of the lottery system is given by Joy Sperling, ‘Art Cheap and Good: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840-60’, www.19thc-artworldwide.org: ‘The "Art Union" was a nineteenth-century institution of art patronage organized on the principle of joint association by which the revenue from small individual annual membership fees was spent (after operating costs) on contemporary art, which was then redistributed among the membership by lot. The concept originated in Switzerland about 1800 and spread to some twenty locations in the German principalities by the 1830s. It was introduced to England in the late 1830s on the recommendation of a House of Commons Select Committee investigation at which Gustave Frederick Waagen, director of the Berlin Royal Academy and advocate of art unions, had testified. By 1850 there were some thirty art unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland.’ 16 Roger Smith, 'The Art Unions', in Atterbury (ed.), The Parian Phenomenon, p.26. 17 See also Joy Sperling, 'Art, Cheap and Good: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840-60', in: www.19thc-artworldwide.org . 18 cf. Smith in Atterbury (ed.), The Parian Phenomenon, p.28. 19 Gosse 'The Place of Sculpture in Daily Life'p. 6. The original quote reads, 'La creta è la vita, il gesso è la morte, il marmo è la resurrezione dell'opera d'arte', in MARTINELLI, Valentino Martinelli, 'Canova e la forma neoclassica', in: Arte Neoclassica, Venice 1957, p 204, cf. Roman Stamp, Frame and Façade in Some Forms of Neo-Classicism, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 1974, p.182. 20 cf. Edward Morris, French Art in 19th Century Britain, New Haven/London, 2005, p.258. 21 Pierre Bourdieu, Die Regeln der Kunst, see chapter 'Kunst und Geld. Genese und Struktur des literarischen Feldes', Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 2001, pp. 198-205. (Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art. Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, Stanford, 1996.) 22 cf. Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851-1951, Holme Cardwell, www.sculpture.gla.ac.uk 23 cf. Morris, French Art in 19th Century Britain, p. 257. 24 Ford, 'Section of Sculpture‘, pp.120-121 25 The art historian Johann David Passavant (1787-1861), for instance, reports in his Kunstreise durch England und Belgien, published in 1833 (Tour of a German artist in England, 1836) that French craftsman were employed for the casting of an equestrian statue by Chantrey at the Royal Brass Foundry of Woolwich, vol. 2, p.285, cf. www.npg.org.uk , British bronze sculpture founders and plaster figure makers, 1800-1980, R, The Royal Brass Foundry. 26 cf. exh. cat. 'Gibson to Gilbert. British Sculpture 1840-1914', The Fine Art Society, London, 2nd June - 2nd July 1992, Introduction by Herbert Read, p. 4. 27 cf. Marie Busco, Sir Richard Westmacott: Sculptor, Cambridge 1994, cf. www.npg.org.uk , British bronze sculpture founders and plaster figure makers, 1800-1980, W, Sir Richard Westmacott. 28 Hamo Thornycroft, ‘Lecture on Sculpture. Given at the Royal Academy by Hamo Thornycroft’, 1885, p.44, document held at the Henry Moore Institute Archive, Ti-Y2-2. 29 Ibid, pp.45-46. 30 cf. exh. cat. 'Gibson to Gilbert. British Sculpture 1840-1914', p. 4. 31 Edmund Gosse, 'The New Sculpture, 1879-1894', in Art Journal, 56 (1894), pp.138-42, 199-203, 277-82, 306-11. Edmund Gosse 'The Place of Sculpture in Daily Life', Magazine of Art, 18 (1895), pp.327-29, 368-72, 407-10; 19 (1896), pp. 306-11. 32 cf. exh. cat. 'Gibson to Gilbert. British Sculpture 1840-1914', pp. 3-4. 33 Gosse 'The Place of Sculpture in Daily Life', 1895/1896, pp. 370-372. 34 Spielmann, British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day, pp.1-2. 35 cf. 'The Correspondance of James McNeill Whistler', University of Glasgow, in: www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/ cf. Morris, French Art in 19th Century Britain, p.258. 36 ‘One’s Self I Sing’ in Walt Whitman (1855), ‘Leaves of Grass’, David McKay, Philadelphia, 1900. |

|||||||||||||

From Ceramics to the Bronze Age: Part 2 • Issue 15 |