Interpreting Ceramics | issue 13 | 2011 Articles & Reviews |

|

|||||||

Llanelly Pottery – A Welsh MetonymKathy Talbot |

|

|||||||

|

Abstract Key words: Identity, material culture, Llanelly Pottery, Llanelli, Welsh Industries Association Introduction

The South Wales Pottery, usually referred to as Llanelly Pottery, which opened in Llanelli in 1840, was a small commercial enterprise, producing utility and decorative objects for a largely local market. It continued in production until the 1920s and at no time were its wares described as high quality. However, these largely ephemeral goods are now valued as symbols of local heritage and identity. Beyond personal and local identity the Pottery’s production reflected the tension between an English and a Welsh identity.1 In the nineteenth century there was a huge increase in the popularity of decorative ceramic items in the home, of which Staffordshire flat-backs are the best known. Writing in 1903 Henry Willett, a wealthy collector of ceramics, described them as ‘homely pottery…a kind of unconscious survival of the Lares and Penates [household gods] of the Ancients’.2 Herbert Read the art critic, who was assistant in the Ceramics Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in his seminal text published in 1929, viewed them as ‘simple cottage ornaments… full of unconscious artistry’ intended for the decoration of lower-class homes.3 This is the context of Llanelly Pottery’s production, intended for lower-class domestic consumption, providing utility and decorative ware, which was emulative of hand-decorated fine china from Staffordshire potteries such as Minton or Copeland. Victor Buchli argued that the modes of consumption and the ‘ephemerality of the fashion system’4 since the late nineteenth century made the material artefact inappropriate as a means of sustaining identity. However, Deborah Cohen observed that the minutiae of domestic decoration, including domestic ceramics and utility wares, were more indicative of a Victorian lifestyle than the high-class, sophisticated designed objects later found in museums.5 Retained and valued in a family context and later collectable, the wares of the Llanelly Pottery became the wares of Llanelly Pottery became signifiers of cultural and economic capital and identity. Identity is a fundamental facet of the structure of society. It is the means by which individuals, groups or nations differentiate themselves from one another. Identity is a construction, a collection of past and present, inherited or acquired traits, habits and culture. While some indicators of identity are intangible, the material culture of society is the physical evidence by which identity is conveyed, imposed and understood and locates one in social hierarchies. These same items of material culture which delineate identity can also act as foci of nostalgic emotions, which are equally as subjective and variable as the presentation of identity. The wares produced by the Llanelly Pottery would not find themselves in many major collections, although they are valued in the context of Wales, as individual pieces and in private and public collections.6 The items discussed in this paper are not figurines such as Willetts and Read referred to but a particular range of hand-painted wares, produced in the period 1877 to 1920. In 1877 two cousins, David Guest and Richard Dewsberry, both with family connections in Stoke-on-Trent, reopened the Llanelly Pottery and introduced a range of new and fresh hand-painted wares. Several of the designs used, such as the cockerel, chicken and hen as well as floral motifs, were copied from other potteries of the period including Wemyss in Scotland, Pountneys in Bristol and potteries of South Devon. However, despite the designs used at Llanelly Pottery not being authentic, unique or original to the Pottery, they would have much greater significance to local identity than wares of those potteries from which they had adopted and adapted the designs. Foremost, amongst those collected are the cockerel plates, made of a poor pottery body and decorated with a naïvely painted motif and sponged border. They came to act as signifiers of identity and nostalgia for the area.

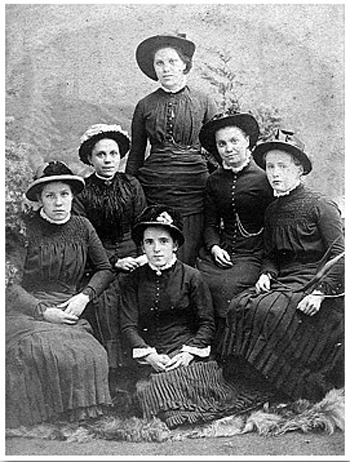

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century nostalgia developed as a cultural practice in Britain in order to assuage the non-beneficial aspects of industrialisation and changes in society’s structure. Nostalgia for an idyllic rural past, for stability, certainty and fresh air, recalled from the comfort of improved social conditions and technological developments, prevailed over recollection of the hardship of an agrarian society with its hard work, long hours and poverty. The industrialised town of Llanelli, where the population had grown from 500 in 1728 to 7123 in 1841 when the Pottery opened and to 36,520 by 1921was an example of mass migration from an agricultural hinterland to an industrialised economy based on copper, coal and later tinplate.7 The town of Llanelli was described as a microcosm of Welsh society, in terms of its geographical location, language and temperament.8 The Pottery was part of this distinct location. The hand-painted items marketed by the Pottery from the late 1870s, with colourful motifs related to the farmyard and the sea, could be used to distance the house and home from the dirty and harsh working environments in the coalmines and tin plate works. As Dilys Jenkins observed, they were best when seen ‘in a small house, a cottage, on a Welsh dresser, or in an alcove where the bright colours may add light to a dark corner’.9 The stimulus to purchase or possess ‘things’ can be varied, conscious or unconscious and, on a fundamental level, may be solely for survival and comfort. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Christopher Tilley stated that objects function in three different, complementary ways to locate people in society. Objects demonstrate position in a social hierarchy, provide a focus for memories and thus continuity, and thirdly provide evidence of valued social relationships. People need material goods to ‘objectify the self, organise the mind, demonstrate power and symbolise their place in society’.10 However, despite their objective nature, the ownership and mode of display of decorative and utility objects in a home are subjective. They are key elements in the way in which people create, maintain or modify identity and define their heritage. These objects, personally selected and displayed, are signs by which others can interpret and ascribe identity, but from their own subjective experience and knowledge. dichotomy of Welsh or English identity Llanelly Pottery in the late nineteenth century was part of a Welsh society and social structure that strove to reconcile the desire for a national identity with the needs of operating within an English hegemony. Over the centuries the identity of Wales as a distinct nation was challenged by the dominance of the English and English language. In the late nineteenth century the contentious issue of a Welsh versus an English identity fuelled by the ‘Blue Books’ published in 1847 was still current.11 The Blue Books were seen as a threat to the culture of Wales and provided a focus for nationalism and the birth of Welsh devolution. However, identification with Wales, Welsh culture and language was countered by the demand for education in and use of English language which were seen as necessary for social and economic advancement. Many preferred to call themselves ‘English’. For example, Thomas Roberts, the nephew of one of the Pottery’s paintresses, Sarah Roberts, when writing home in World War I before his death at Ypres, referred specifically to ‘we English’.12 There was a dichotomy between the wish to reject the English supremacy and colonial attitudes and the realisation that in order to achieve self-determination it was necessary to partake in the dominant English institutions. ‘Made in Wales’ or the use of Welsh-style motifs were not popular on Welsh-produced pottery, which was competing with the perceived superiority of English wares from Stoke-on-Trent. The taste for English, as opposed to Welsh, manufactured goods was encouraged by local china dealers who advertised only Staffordshire pottery. Newarks’ China Depot at 26 Market St Llanelly advertised ‘Royal Worcester, Doulton and Wedgwood’, and did not mention the local pottery.13 For the upper classes, purchase of Staffordshire pottery was supported by interior decoration advice texts, such as Robert Edis’ Decoration and Furniture of Town Houses, which recommended Wedgwood, Minton, Doulton and Royal Worcester.14 The Decorators – the importance of the individual Although there were several decorators working at the Pottery only two have become renowned for their contribution. Samuel Shufflebotham was well travelled, trained and recruited from an English pottery. The other, Sarah Roberts, lived all her life in Llanelli and received no training in china painting other than when working in the Pottery. Samuel Shufflebotham (1876-1939) In 1908 a pottery decorator, Samuel Shufflebotham, moved to Llanelly Pottery. Raised in the Potteries, by the age of 14 he was already recorded as a ‘potter’s earthenware painter’ in Hanley; ten years later in 1901 he moved to Bristol to work for Pountney & Co and Dorset potteries. In 1908 he was recruited by Richard Guest for the Llanelly Pottery.15 Richard Guest, with family connections in the Staffordshire potteries and a regular visitor to London, would have become aware of the interest in folk wares and also the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the aspirational taste for the ‘hand-finished’. How and why he chose Samuel Shufflebotham particularly, when there would have been other similarly experienced decorators, is not known. Shufflebotham brought with him many of the designs he had painted or observed at Pountneys; such as the Wemyss style roses and Cock and Hen, as well as the cockerel. Dutch figures, cottages and sailing boat designs were introduced from his period at the Crown Dorset Pottery in Poole16 The Llanelly Pottery was therefore providing the local market with goods of similar appearance to the more valued English potteries. Shufflebotham was a skilled decorator throughout his career and it can be difficult to distinguish his Bristol work from his work at Llanelly. However the plates, plaques and other items known to have been decorated by him at Llanelly now command comparatively higher prices. At the time his reputation was augmented when he was commissioned to paint plaques for a member of the local gentry, Lady Howard Stepney.17 Sarah Jane Roberts (1859-1935) In contrast to Samuel Shufflebotham’s varied experience in Staffordshire, Bristol and Dorset potteries, the other renowned decorator at the Llanelly Pottery, Sarah Roberts, popularly referred to as ‘Aunt Sal’, never moved from Llanelli and had no training outside of the Pottery. Her work has a free, naïve quality different from the more assured, naturalistic style of Shufflebotham. Sarah Roberts and her four sisters were all employed as paintresses in the 1880s and 1890s, although only she remained in the Pottery until its closure in 1922.18 They were the daughters of Thomas Roberts, pottery kiln worker.19 Women were employed in packing and other departments including transfer printing, which represented the majority of the production between 1855 and 1875 and continued until the Pottery’s closure in 1922. Sarah Roberts had probably started work in the Pottery in about 1873 when, as Shufflebotham when he had started work in Staffordshire, she was aged 14. Her younger sisters followed her at a later date. (Fig 3) Despite their apparent skill with the brush, none of them is believed to have received any education beyond the most basic and there is no record that they attended the local art schools or evening classes.20 Initial instruction in hand painting was possibly received from the two female decorators recruited from Stoke. The 1881 census recorded seven paintresses, including Jane Simcoe and Maria Davies from Burslem, working in the Pottery.

Top of the page | Download Word document | Continued Notes To return to the article click the relevant note number 1 For a full history of the pottery see D. Jenkins, Llanelly Pottery, Swansea, Watkins, 1968, G.Hughes and R. Pugh, Llanelly Pottery, Llanelli, Llanelli Borough Council, 1990. The South Wales Pottery first opened in 1840. From 1877 it was operated by the partnership of Guest and Dewsberry and became a limited company in 1910. Although it is sometimes known by these different names, it is generally referred to in the literature and by collectors as ‘Llanelly Pottery’ and is so referred to in this study. The spelling of the town was changed in the mid twentieth century to ‘Llanelli’ and this style will be used to denote the town, unless referenced from early articles and texts.2 Catalogue of the 1903 exhibition in Brighton Museum of Henry Willett’s collection. 3 H. Read, Staffordshire Pottery Figures, London, Duckworth, 1929, p.20. 4 V. Buchli, ed. The Material Culture Reader, London, Berg, 2002, p.15. 5 D. Cohen, Household Gods, the British and their possessions, London, Yale University Press, p. xv. 2006. 6 The main collection is at Parc Howard, Llanelli and there are also examples in Carmarthen Museum, Abergwili, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff. 7 Michael Scott Archer, The Welsh Postal Towns before1840, London, Phillimore, 1970 and Llanelli Library census records. 8 H.M. Jones, Llanelli Lives, Gwasg y Draenog, 2000, foreword by Sir David Mansel Lewis. 9 D. Jenkins, Llanelly Pottery, p.9. 10 C.Tilley, W. Keane, et al., eds. Handbook of Material Culture, London, Sage. p. 6,1 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, ‘Why We Need Things’, S.Lubar, and W. D. Kingery, eds. History from Things, Smithsonian Institute Press.1993, p.23. 11 G.A.Williams, When was Wales? London, Penguin, 1991,.p.208. 12 Conversation with niece of Sarah Roberts, Mrs June Sinclair, 8th August 2007. Thomas Roberts died at the Battle of Ypres on 24th May 1915. 13 Llanelly Mercury, 2nd January 1912. 14 R.W. Edis, Decoration & furniture of town houses. London, Kegan Paul, 1981,. p.246. 15 Both David Guest and Richard Dewsberry had died by 1906. Richard Guest, David Guest’s son, took over as sole proprietor before the Pottery became a limited company in 1910. 16 Honiton Pottery Collectors Society, no. 4 25, June 1992, and correspondence with J. Allen, collector. 17 D. Jenkins, Llanelly Pottery, p.42. Lady Howard Stepney, daughter of Lady Cowell Stepney, was the wife of Sir Edward Stafford Howard, Charter Mayor of Llanelli. 18 Ann Roberts, b. 1856, Sarah Roberts, b. 1859, Margaret b. 1866, Elizabeth b. 1869, Emma, b. 1875. A brother, John Roberts b. 1863 was listed as a painter in 1881 but later took over the family greengrocer and florist business. Sarah Jane Roberts never married and worked at the family greengrocers following the pottery’s closure. 19 Thomas Roberts later retired from the pottery and became a market-gardener. 20 Interview of Mrs June Sinclair, great niece of Sarah Roberts, Llanelli, 8th August 2007. |

||||||||

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated |

||||||||

Llanelly Pottery – A Welsh Metonym • Issue 13 |