Interpreting Ceramics | issue 13 | 2011 Articles & Reviews |

|

|||||||

Museums and the 'Interstices of Domestic Life':Re-articulating Domestic Space in Contemporary Ceramics Practice

Laura Gray |

|

|||||||

|

Abstract Key words: Edmund de Waal, Clare Twomey, Anders Ruhwald, domestic, exhibitions Ceramics and Domestic Space There are two main strands to the history of displaying ceramics in domestic space prior to the twentieth century: the porcelain rooms of palaces and stately homes; and the more familiar type of domestic space in which most people encounter ceramics– the kitchen dresser, the mantelpiece, ornaments clustered on tables and shelves. Drawing attention to the princely palace or stately home as a site for the display of ceramics serves only to remind us that historically, there have been instances where high status examples of such work, porcelain particularly, have been exhibited in high status domestic space, an environment also considered eminently suitable for the display of paintings and sculpture. Such palaces, of course, served a public, even a state function, as well as containing more private domestic space. In the modern and post-modern periods, the home has been both an important and an undervalued location for encountering art, particularly ceramics. Important because domestic space is the traditional site for encountering ceramics, and undervalued because of an understanding of domestic space as a female sphere, functional associations, the financial value of objects, and the small scale required for display in the home.2 Nonetheless, certain artists working with clay have chosen to reengage their practice with the domestic – either in terms of the exhibiting site or through engagement with ideas. This article endeavours to understand how and why artists working with clay have sought to return their work to a domestic context or create an association with a type of location that through the modern period was constructed as the antithesis of serious art. The exhibition A Secret History of Clay: From Gauguin to Gormley (Tate Liverpool, 2004) touched on ideas relating to ceramics and the domestic. Amy Dickson, who worked on the exhibition as assistant curator explained in an interview conducted in 2010 how ideas around the domestic were explored in the exhibition:

The final room of the exhibition, which showed a Cindy Sherman tea set, ceramics by Jeff Koons, ceramic brooms by Richard Slee, and a version of Edmund de Waal’s Porcelain Wall, presented ceramic practices that had reengaged with the domestic environment, but prioritized the concept of the domestic over the physical location of the home. The restitution of the domestic as an element in a strand of contemporary ceramics can be seen to indicate a practice that has developed beyond the straightforwardly functional, even when works reference the domestic and take the form of theoretically utilitarian objects such as de Waal’s vessels or Sherman’s tea set. Though these works might reference domestic objects or the home, they behave squarely as art objects, rather than things to be used. Tanya Harrod suggests that ceramics have, as participants in the fluctuating relationship between art, craft and the home, ‘over the centuries, carried all kinds of high and low art references into the domestic space’.4 Colin Painter writes in the catalogue for his exhibition At Home With Art (Tate Britain, 1999), that ‘distinctions between the functional and non-functional are often blurred. It is in this combination of roles and meanings that art can become part of life’.5 This article sets out to demonstrate that the work of Edmund de Waal, Clare Twomey and Anders Ruhwald takes advantage of this blurring and combining of roles to test and experiment with the expected role of ceramics in relation to the domestic. The Separation of Art and the Home From the early twentieth century, in the wake of the Arts and Crafts movement, domestic space was repositioned ‘as the antipode to high art’.6 Christopher Reed quotes Russian artist Alexandr Rodchenko as saying, ‘the art of the future will not be the cosy decoration of family homes’.7 Reed goes on to suggest Dada and Surrealist artists too, with their fascination with the uncanny habitually ‘appropriated the accoutrements of domesticity in ways that undermined connotations of homey comfort, while the theoreticians of these movements sustained the anti-domestic rhetoric of earlier modernists’.8 So where does the powerful modernist rejection of the domestic, and objects with domestic connotations, leave ceramics, particularly vessels, whose suggestion of function makes the home a natural place to encounter them? If serious art has been banished from the home, what does this mean for the status and perception of ceramics that continue to use vessel forms and so persist in their domestic associations? Even the human scale of most vessel-based ceramics is sufficient to align them with the domestic. Mark Rothko, echoing Rodchenko, announced in the New York Times that his art ‘must insult anyone who is spiritually attuned to interior decoration; pictures for the home; pictures for over the mantel’.9 In answer to the call from some artists, including Rodchenko and Rothko, for art not be brought into contact with the everyday (often the scale of works inhibited display in homes), and as part of the desire to find a new kind of space for encountering art, the stark modernism of the ‘white cube’ gallery emerged in the 1920s and 1930s. In America, 1929 saw the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. MoMA’s founding director, Alfred Barr, did not select the paintings for the museums inaugural exhibition, but he did install them. Barr covered the walls with a natural coloured cloth and eliminated the salon style of hanging paintings. This type of installation looks rather unexceptional now, as this manner of presenting paintings has become so conventional that its significance is completely invisible. But the exhibition contributed to the introduction of a particular type of installation that came to dominate museum practices, whereby the language of display articulates a modernist, seemingly autonomous aestheticism.10 MoMA’s 1934 exhibition Machine Art is an example of the simple, spare, pared-down aesthetic which became, and remains, the standard environment in which to view art. This type of presentation of art was a part of the new methodology of display. The development of ‘white cube’ spaces for the display of art facilitated a severance of art from the domestic elements that had previously been found in exhibition spaces (such as seating, or the ‘country house’ approach to the display of artworks which incorporated richly coloured walls and dense hangs of paintings). Yet, despite the stark, white spaces of the modern art gallery having become synonymous with the display of art that has ‘intellectual significance’, artists working with clay have, over the last decade, returned to the domestic environment. Ceramics, after attempts in some quarters to distance the medium from its domestic associations, returned to the home. Artists such as Clare Twomey and Edmund de Waal, with an artistic practice that engages with installation, and the site-sensitive or site-specific, have, on a number of occasions, chosen house museums as a site for their work. In such instances, the house museum not only offers a frame for the work, but becomes part of the work itself. Though in England the concept of the public visiting great houses to see their art collections while the owners were away isn’t new, what has changed is the way that artists are actively using the space in which their work is located. The work does not sit passively, but has an active relationship with the environment that it inhabits. Contemporary Ceramics and a Reengagement with Domestic Space The distinction between the ‘thing’ and the ‘object’ is the pivot on which an understanding of the role that contemporary ceramics can play in a domestic setting turns. Louise Mazanti writes of the difference between thing and object, arguing that:

She continues, considering object and thing in relation to perception and interpretation,

In this instance, Mazanti is shaping her ideas in relation to the work of Anders Ruhwald, for whose exhibition catalogue her essay was written. The key difference that Mazanti identifies between object and thing is the source of meaning and whether that comes from within or without.

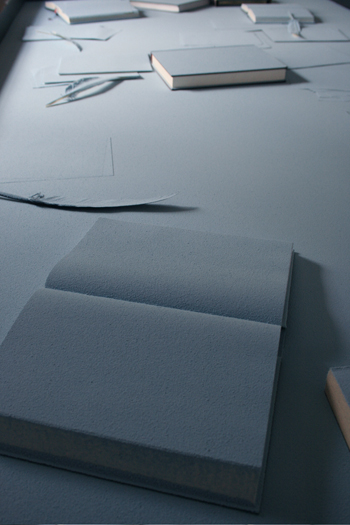

The work of both Edmund de Waal and Anders Ruhwald explores the difference between thing and object, and in doing so, disrupts expectation, including the expectation of the conceptual boundaries of artist practice that uses ceramics as a source of meaning and material. The use of domestic imagery, association or location further destabilises the expectations that surround ceramics, particularly vessels. As the work of de Waal demonstrates, the vessel has returned to the domestic environment, but it is a changed vessel, and it is occupying the space on its own terms. There has been a transition from thing to object that allows pots to sit in domestic space but speak the language of sculpture, rather than the language of craft and utility. In the case of de Waal, domestic space has become the site for a more sculptural ceramics practice, a practice that undermines distinctions between sculpture and functional objects. In the aftermath of the modernist insistence of the separation of the home and the display of art, de Waal has successfully reasserted the domestic environment as a legitimate site of encounter with his artistic practice. This repositioning can be seen as having two stages: firstly, encouraging a rethinking of work in clay as part of the mainstream of visual art, and secondly, returning to the domestic environment with this work, not with, for example, what Reed refers to as the ironic detachment of the Pop artists (Roy Lichenstein’s ceramic dinnerware), but with a careful consideration of the space, light and history of the setting, and the movement of the viewer around that space. Edmund de Waal and Clare Twomey have thoughtfully and effectively used the public-private space of house museums for their installations. The installation-like nature of their work uses to advantage what Gill Perry identifies as the fluid nature of the viewer’s experience when encountering installation art, in contrast to ‘the clearly defined object in the white cube’.14 In a domestic space, even one that has become a museum, more layers of meaning are possible. Encountering their work in such setting is not simply about attractive placement. For de Waal and Twomey, the museum becomes part of the medium. Largely as a consequence of de Waal’s success in working in this way, the engagement between ceramics and curatorial practice that occurs in the practice of those artists that use the house museum has become an important strand of practice in contemporary ceramics, particularly for those artists who work in the vessel/installation/sculpture continuum. Twomey is less focused on the vessel form than de Waal, though one of her most powerful works to date, Monument (mima, Middlesborough Institute of ModernArt, 2009), was made up of a towering heap of domestic ware, which demonstrated not only the powerful effect of massed objects, but the sense of disquiet that seeing broken plates and cups could cause. Monument was testament to the continued relevance of the vessel in a greatly expanded ceramics practice. Twomey has also created a number of works specifically for house museums. In 2009 she was commissioned to create a work to form part of an exhibition that celebrated the tercentenary of the birth of English lexicographer Dr Samuel Johnson. Twomey’s work Scribe was displayed as part of the exhibition House of Words at Dr Johnson's House. Beneath a layer of pale blue dust there lies books, paper, quills as if the users of these writing materials have abandoned them at a time of great activity, and have simply never returned. This installation that Twomey created in the garret room of the house pays homage to the six assistants who supported Johnson in his work on his Dictionary of the English Language. The thick layer of blue dust that covers the books, feather quills and stacked papers was created from Wedgwood blue Jasper clay.

Twomey has used blue Jasper clay in her work before, as dust and to make objects. This particular type of clay opens up the work to numerous possible associated meanings. There are shared associations between Wedgwood and Johnson, two great figures of eighteenth century England, who both came from the Midlands. The poignancy of abandoned writing materials left, Miss Havisham-like, to accumulate dust. And the dust itself, creating an association with a struggling ceramics industry, mothballed factories and lost skills. Twomey’s dialogue with the house does not acknowledge the space as a domestic environment, though it was, for a period, both home and workplace for Johnson when compiling his Dictionary. Where de Waal would have perhaps pursued an engagement with architecture and space, Twomey engages with the memories contained within the building. A connection with the ephemeral made with an ephemeral material. Though she does not ignore the history of the building, Twomey’s work uses the house museum and its history as a starting point for the exploration of more universal strands of thought, such as memory and the passing of time. Her use of dust, butterflies, flowers and birds as motifs in her work evidence these themes, which display a Keatsean preoccupation with transience and permanence. A recent installation by Twomey, A Dark Day in Paradise, which is made up of thousands of ceramic butterflies, was created for the Royal Pavilion in Brighton in 2010. Twomey’s three thousand black-glazed ceramic butterflies swarmed, hovered and rested in the decadent interior of the dining room of this exotic royal pleasure palace, built in stages for the Prince Regent, later King George IV, between 1787 and 1823.

Not wholly gorgeous to encounter, the glistening black butterflies are transformed into something more unsettling as they crawl over the fruit on the dining table. Twomey has described her concept for this piece as being that a swarm of unsavoury but very beautiful butterflies have landed in the pavilion and they’re judging it in some way. Twomey also explained the cloud of butterflies as a romantic image, which have become part of the inescapable, and at time overwhelming, romance of the building.15 Her idea was to try to embed them, to give the impression that they’ve always been there and unsettle the visitors who are unsure whether the butterflies are part of the historic interior: an enterprise that could only have taken place in a building with as extravagant an interior as this one. Twomey described the pavilion as a very difficult environment to make for because the interior of the building is so overwhelming; making competing with the decoration for the visitor’s attention almost impossible. Nevertheless, the building, with its particular history and associations, allowed her work to have a dialogue in a very particular language that only exists there, in that building. And it is that particular dialogue, the collaborative element, different in every one of the house museums that makes such places rich collaborative partners for contemporary ceramics practice. Top of the page | Download Word document | Continued Notes To return to the article click the relevant note number 1 See J. Putnam, Art and Artifact: The Museum as Medium, London, Thames and Hudson, 2009 (revised edition) and also E. de Waal, S. Kuhn, J Putnam, et al, Arcanum: Mapping 18th Century European Porcelain, Cardiff, National Museum Wales, 2005. 2 M. Vincentelli, Women and Ceramics: Gendered Vessels, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000, p.128. 3 Author’s interview with Amy Dickson, assistant curator, Tate Modern, 2010. 4 T. Harrod, ‘House Trained Objects: Notes Toward Writing an Alternative History of Modern Art’, in C. Painter, editor, Contemporary Art and the Home, Oxford, Berg, 2002, p.70. 5 Colin Painter, At Home With Art, London, Hayward Gallery, 1999, p.5. 6 Christopher Reed, ‘Introduction’, in C. Reed, editor, Not at Home’: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture, London, Thames and Hudson, 1996, p.7. 7 Quote taken from Solomon-Godeau, cited in C. Reed, ‘Domestic Disturbances: Challenging the Anti-domestic Modern’, in C. Painter, editor, Contemporary Art and the Home, Oxford, Berg, 2002, p.39. 8 Reed, ‘Domestic Disturbances’, p.39. 9 Cited in Reed, ‘Domestic Disturbances’, p.41. 10 M. Staniszewski, The Power of Display: A History of Exhibition Installations at the Museum of Modern Art, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 2001, p.61. 11 L. Mazanti, ‘Life among objects and life among things’, in J. Beighton and A. Ruhwald, editors, Anders Ruhwald - You In Between, Middlesbrough, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, 2008, p.57. 12 Mazanti, ‘Life among objects and life among things’, p.57. 13 Ibid. 14 Gill Perry, ‘Dream Houses: installations and the home’, in G. Perry and P. Wood, editors, Themes in Contemporary Art, New Haven, Yale, 2004, pp.231-276. 15 Author’s interview with Clare Twomey, 2010. |

||||||||

© The copyright of all the images in this article rests with the author unless otherwise stated |

||||||||

Museums and the 'Interstices of Domestic Life' • Issue 13 |