Interpreting Ceramics | issue 16 | 2015 Articles, Reviews & Reports |

|

|||||||

|

Exhibition review by Anthony Merino ‘Body and Soul: New International Ceramics’ Museum of Art and Design, New York. |

|

|||||||

|

Meeting of the Grotesque and the Kitsch In a broad sense, the grotesque and the kitsch serve one function through opposite methods subverting the norm. The grotesque takes a heat gun to the veneer of civility we put on reality and strips it away. This process renders the nasty, uncomfortable, and harsh nature of the human condition bare. Kitsch layers reality with veneers until it depicts only the most shadowy and polished sentiment of reality. A majority of the artists in ‘Body and Soul: New International Ceramics’ employ one or both of these styles to provoke the viewer. Quite a few artists referenced both grotesque and kitsch elements in their work. Jessica Harrison masterly combines both genres to create haunting images. Using epoxy resin and enamel paint, the artist mutilates found porcelain figurines. The original pieces are essentially pastoral icons of an imagined era when women understood the allure of demur femininity. Ironically, Harrison endows the figures with more individuality than the original object. The artist coaxes nuance and subtle affects out of vulgar and base mutations. In Andrea, Harrison sculpts the figure holding its decapitated head out in front of its body. The impossibility and absurdity of this makes the work morbidly amusing. In contrast, Harrison only halfway severs the neck in Mairi. Absent the absurdity of Andrea, this piece becomes far more disquieting. The artist’s most breathtakingly disturbing piece was Ethel. The figurine’s left arm holds the intestinal debris as the figure disembowels itself. This work becomes an emblem of anorexia. The female figure directs her mutilation in order to fit an abstracted and unattainable ideal of beauty.

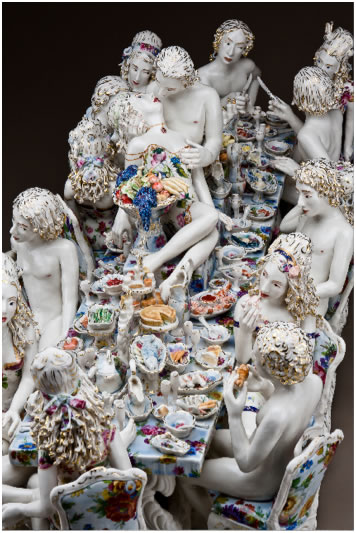

Two other of the exhibition’s artists also successfully meld grotesque and kitsch elements in their work. Chris Antemann in collaboration with Kendrick Moholt displayed a photograph on archival paper of one of the artist’s sculptures. The image Feast of Impropriety depicts a menagerie of naked figurines indulging in a feast of gastronomic and cardinal excess. The figures actions cast them as grotesque. The figurines and heavy saturation of floral images clearly reflects kitsch. Antemann replaces Harrison’s earnestness with a sense of indulgence. The work reads as 51% condemnation and 49% celebration.

Mournir Fatmi turns the grotesque into kitsch in Forget, with ten black skulls set in hard hats. The work intends to depict the brutal conditions of construction and mining workers. The skull clearly references death. This context is undermined by the artist leaving the teeth white. This design is uncomfortably similar to the practice of black face. This cultural reference reframes the content of the piece. At best, Fatmi’s work operates as a mirror and casts the viewer, who profits from the despair of the miners, as culpable. At worse, the piece trivializes its subject by mocking its source material by relating it to institutionalized western racism.

The largest linked group of artists in Body and Soul: New International Ceramics included several artists who use just grotesque elements to elicit empathy from the viewer. Like Harrison, Tip Toland’s disconcerting images subvert gender ideals. The artist refuses the viewer any comfort in Grace Flirt. A life-sized sculpture of a pubescent woman with engorged lips painted with crimson lipstick. By perversely exaggerating both the color and shape of the lips, Toland depicts a disturbing image of inappropriate sexuality. The figure leans forward toward the viewer as if wanting to engage. At the same time its arms are crossed over its torso in a defensive posture. With acute skill at rendering human features and gesture, Toland creates an arresting image of vulnerability and pathos. Michel Gouéry shocks the viewer using surrealism. Gouéry contributes two of the exhibition’s most disturbing images in Riri and Fifi, two life-sized seated female figures. The artist replaces the skin with beaded and stitched leather. In place of heads, Gouéry places two perverse helmets. One has a gapping instead of a face, the other looks like a robotic cricket. The abdomen of each figure looks life like, but the extremities look as if they were empty. This single detail creates a chilling narrative of a figure with its identity scoured. All of these artists are stylistically very polished and refined. Body and Soul includes several artists whose work is primitive. Two stand out among this group. Daphné Corregan displays a bust Smeared Face where the eyes are covered with a mask and the nose and lips a dry red. Sourced from the artist’s encounters with war victims in Africa and the former Yugoslavia, the image reflects an archetype of the tragic harlequin. Kiara Kristalova contributes one of the exhibition’s most horrific images, Hollow. The figure’s face is gutted. Kristalova renders the work with a mannered clumsiness that creates an aura of authenticity. The unskilled appearance of Hallow makes it read as a document not an image. Several other artists included images that are equally unpolished, while only Teresa Girones image generates the same resonance. Like Corregan and Kristalova, Girones evokes empathy from the viewer. Many other artists include works that are as roughly rendered but not as successful. Some artist did work that was exclusively derived from kitsch. Kim Simmonsson contributed near life size sculptures look like warped Precious Moment figurines. Commenting on this, the artist states, “I play the game of innocence. Children and animals are my actors. They present disturbing acts that are not expected of them. Sometimes the aesthetic surface almost hides the terror.” Carrie II, the subject appropriated from the Stephen King novel, depicts a young figure with its head bowed and what looks like tar dripping from its heavy locks. In Untitled, Simonsson places two children, male and female on their knees facing a female child. The female child holds gun behind her back. This play of horrific narratives articulated with saccharine icons creates very creepy images. Valérie Delarue and Elsa Sahal contributed works that were far too cryptic to be grotesque or kitsch but were as fascinating as most of the other works included in the exhibition. Delarue showed Corps au Travail (Body of Work) a video work in which the artist does slow acrobatics and dance in a room with a wet clay floor and walls. Almost clinical, it portrays a contorting female nude but has almost no erotic or voyeuristic content. On a high abstract level, the artist reverses the relationship between material and maker. In this work the artist must bend to the will of the material. Sahal creates a sense of monumentality in Black Feet, a pair of feet under two tapered and elongated orbs. The only definitive assumption you can make from the work is that the feet are the only direct image. From this the artist allows the viewer to invest in the image whatever meaning they can. The dichotomy of grotesque and kitsch is based on a conceptual linkage. All of the substance under the surface of existence either actually, like guts or blood, or metaphorical like politics and human cruelty, are repulsive. Everything layered on top is disingenuous. The best artists in Body and Soul use these associations to move the viewer toward anger or empathy. Clay is the material they work with. Human perception and emotions are their media. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

||||||||

Exhibition review by Anthony Merino • Issue 16 |