Interpreting Ceramics | issue 17 | 2016 Articles, Reviews |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

African Pottery, studio pottery and contemporary ceramics on display: Sankofa, Ceramic Tales from Africaby Moira Vincentelli, Aberystwyth University |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract

Problems of Classification Writing in a review of Convention, Context, Change Gary van Wyck expresses some reservations about ‘the relativist logic of the postmodern position’ but suggests that ‘criteria for discriminating between Western and African artworks are extrinsic, conventional and largely arbitrary’.1 Classification is indeed a shifting field in relation to art in Africa and further confused by the problematic relationship between words such as ceramics and pottery. Ceramics is now the more inclusive term to reflect the broad range of clay production and activity - from functional artefacts through to sculpture and the ‘expanded field’ of conceptual work and installation. Some makers call themselves potters in defiance of the new tendencies and ‘studio pottery’ now refers to a distinctly twentieth century historical movement. This has implications for African ceramics where issues of ‘authenticity’, ‘age’ and ‘tradition’ are given high value and, with some exceptions, new forms and modernity are often treated with suspicion. Over the last quarter century the relationship between contemporary African art and the context in which it is viewed has changed radically, a regular flow of exhibitions and publications have been seen beyond the continent. The transformation of the journal African Arts is witness to this process with its extensive coverage of contemporary art. Nevertheless, I do not think that ceramics have fared well in comparison with other visual arts. African ceramics are primarily based on domestic low-fired technologies and as such are usually referred to as pottery. New versions do not travel well - either physically or metaphorically. Furthermore there are gender implications when such a high proportion of the potters are women. The ceramics at Aberystwyth University were acquired in the interwar years as part of an ‘Arts and Crafts’ collection to support teacher training. Those responsible for acquisitions had collected widely from British prints, studio pottery and world crafts ranging from Welsh love spoons to North American baskets and even some North African pottery from Kabylie. The collection had largely been put into storage between 1940-75 and, when it was decided to revive it, the focus was to be on ceramics and prints. Some parts of the early collection were redistributed to other museums.

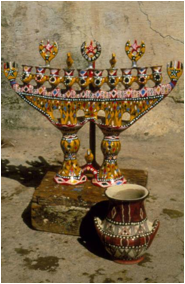

What had once been seen as a whole – in an arts and crafts collection, by the 1970s and 1980s, was divided and classified in new ways. Objects were separated across the Nature – Culture divide; ‘anonymous example of craft work’ as opposed to ‘individual art work’ whether print or ceramics. The Kabyle candelabra (Fig.2) no longer seemed appropriate to show alongside the pioneer pottery of Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada and Michael Cardew (Fig.3), although they are in fact from the same period.2 On my research trip to Kabylie in Algeria I was faced with another problem of classification in relation to decoration. I found many potters were still producing pottery not dissimilar to the examples we had from the 1920s. Some of the potters, however, were decorating the pottery with household gloss paint rather than the more muted earth colours made from local materials. This clashed with the values of twentieth century studio potters, with moral prerogatives of ‘honesty’ and ‘truth to materials’. Gloss paint is not a ‘ceramic’ material but it clearly had popular appeal for the main audience, the Berber peoples living in the towns and villages in that region (Fig.4). 3

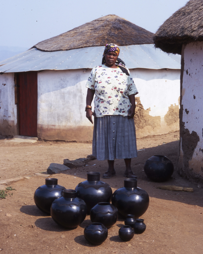

International Ceramics Festival In the late 1980s we began to hold a biennial ceramics festival in Aberystwyth where international demonstrators were invited. We received considerable publicity in 1989 when we had two potters from Nigeria as demonstrators (Fig.5). Asabe Magaji from Tatiko and Assibi Iddo from Nigeria were accompanied by Michael OBrien who had taken over at Abuja Pottery4 after Michael Cardew had left. They demonstrated their technique but also bonfired successfully a whole group of pottery. At that point we purchased some works for the collection. The Nigerian potters were a huge success but the event also attracted murmurings about ‘an inconvenient memory of colonialism’, a phrase used by Tanya Harrod in her review of the event.5 Nevertheless over the years at the festival we have frequently had at least one demonstrator showing a contemporary version of indigenous ceramic practices. Sometimes this has been alongside new developments as was the case in 2001 when we invited potters from KwaZulu Natal. Jabu Nala demonstrated the black pottery from her indigenous practice and Wonderboy Nxumalo (1975-2008) from Ardmore Pottery colourful decoration. In the 1990s I continued my research on gender and world ceramics with further field trips and documentation.

All these factors came into play in 2004 when I was invited by Manchester Museum, a museum of natural history, to research an exhibition about contemporary African ceramics and collect material on their behalf. This led to the exhibition Sankofa, Ceramic Tales from Africa. We chose the title based on the Ghanaian Adinkra symbol of the sankofa bird, which looks behind arching its neck backwards (Fig.6). It is often used to suggest the idea of learning from the past in order to move forward into the future. It seemed an apt symbol for so much African ceramics.

The four countries I visited between 2004-5 were Tunisia, Morocco, Ghana and South Africa. The second part of the title ‘Ceramic Tales from Africa’ was intended to suggest the personal and serendipitous nature of what I saw and collected. I did not have the luxury of long research periods in the countries or the experience of living there. In Manchester I worked with the designer, Jeff Horsely, and we looked at both the material that I had collected and the photographs. I wanted to show the social context of production and give some indication of the consumption alongside the work itself. The designer decided to develop an exhibition that would have different forms of display to suggest the varying contexts of the ceramics. The museum purchased some pieces of furniture at auction as well as raiding its own supply of cases and shelves. None of the furniture was in itself anything to do with Africa – so there was a complete contrast there, but it was intended to suggest parallel settings and hopefully allow the audience to make readings by association (Fig.7). In the meantime the photographs, some blown up to a large scale, were used to show the potters in their own environment, sometimes working and sometimes posed for the camera usually with their work beside them. The display suggested a wide range of perspectives from the single piece on a plinth under a perspex cover to elegantly decorated Moroccan earthenware in a small display dresser with a glass front.

More problematic to me was the modern Ghanaian pots shown on metal shelving as in a museum store (Fig.8). ‘Museum store look’ is indeed a setting where you might see African or any ceramics for that matter but inevitably there was a hierarchical reading that the audience would be likely to make - that these pieces were somehow of less value. I was uncomfortable.

At the entrance we used a vintage mahogany museum case for a display of colonial influenced wares from Ghana which included some of the museum’s own pieces along with black pottery that I had purchased in Ghana one century later.

I had been shown the older pieces on an earlier visit to Manchester Museum. They are in black pottery with a label ‘Kpandu’ and had been collected in the second decade of the twentieth century. One is a figure holding a bowl in her lap and the other two are in the form of birds, one a bottle and the other a hen on a nest (Fig.9). Clearly a century ago the Kpandu region in the Volta area of Ghana had developed a market for such things presumably for the colonial ex-pat market. They are ‘conversation pieces’, decorative with a secondary function. The black pottery nesting hen is surely influenced by the Staffordshire pottery versions produced from the nineteenth century.6 On my trip to Ghana I was keen to visit this area, which is still noted for its pottery. Fesi Pottery in the Kpandu region was a woman’s enterprise and when we called the potters came out to greet us. Although not quite where they lived, the workshop had an atmosphere of a group compound with children around. There was a large wood-fired kiln which had been constructed a year or two earlier, by a charitable organisation. The potters were quick to explain, however, that they did not use the kiln, as they could not create the distinctive look of their work, which is the black reduction or smoke-fired effect. Their bonfire area was also just nearby and they found that gave them the finish they required. Over generations they had honed their skills in that form of firing and had not adapted happily to the kiln. It was a pattern I have seen all too often where there is a mismatch between the potters’ needs and aid organisations perceptions of what might be an improvement. Fesi Pottery has been well known for its animal ornaments – tortoises, deer and birds but in the early twenty-first century they had been working with a consultant from Accra and had developed a number of ‘modern’ designs including vases, candlesticks and some beautiful bowls with distinctive raised bosses that nevertheless retained the clear identifying factors of their work (Fig.10). 7

Comfort Afuenyo showed me her waterpot in the form of a chicken with other miniature animals on its back. I later saw these in more than one gallery/ pottery shop in Accra selling at the quite high price of 500 cedis. 8 Comfort gave me an explanation of the meaning of the animals. The snail and the tortoise are quiet beasts of the forests that counteract the wild ferocity of the lion that appears on the lid of the waterpot. Do I interpret this as a typical marketing story? Perhaps, but I also see it as related to the rich proverb culture and animal symbolism in Ghana. How appropriate is it to show such a waterpot alongside studio pottery? For example, in the collection at Aberystwyth there are two jugs in the form of birds: one, a pelican jug, by Charles and Nell Vyse from the 1930s (Fig.11) and the other a work by Geoffrey Eastop from 1986 (Fig.12). I don’t have any particular ‘stories’ about these. They stand on their own for the style and period, within a continuum of their type - Art Deco stoneware or post-Picasso ceramics. Visually and creatively all three pieces have much in common but systems of museum classification keep them apart.

In her article on ‘Souvenir Objects in the West African Collections at the Manchester Museum’, Emma Poulter does not mention ceramics at all and deals rather with wood, metal and leather. I suspect that ceramics rarely count as ‘souvenirs’ but nor are they ‘art’ either so equally tend to be marginalised in discussions of museum collections of African art. 9

The exhibition in Aberystwyth was in a very different type of space, much smaller and all within the standard glass cases of the Ceramics Gallery in Aberystwyth Art Centre (Fig.13). We were able to incorporate some of the large images at the back of cases and some at the entrance outside the gallery. The designer, Gwenllian Ashley who had travelled with me in Ghana, had felt strongly that the display in Manchester had lacked a sense of the bright colour and context of the pottery in a setting. So, in this display, we brought in other objects and materials to suggest comparative approaches to design.

The South African beer pots were shown above re-cycled plastic basins and enamelware and a small, branched candlestick from Kabylie was placed alongside a re-cycled metal candlestick (Fig.14). This can suggest the way design forms migrate across materials and that ceramics have been part of that story from the earliest times. In this case both were anonymous makers.

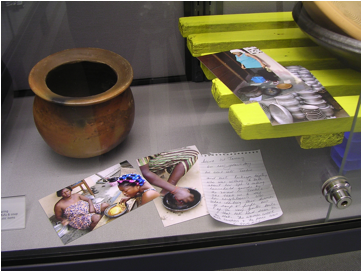

In both displays we were keen to give some sense of travel documentation with small postcard-sized photographs framed up in Manchester. In Aberystwyth this was translated into piles of snapshots with occasional hand-written notes based on the field notes (Fig.15). At the entrance or first showcase we also put in a small stack of guidebooks of the kind that I used. These arrangements did not make for an elegantly laid out exhibition but the aim was to make the process of collecting and display more transparent. It was in general given a good response by the audience. Some specific examples

In Morocco at the huge ceramic production centre at Safi, I met Boutunes Touria who was decorating pre-fired plates with henna using designs derived from henna traditions as opposed to ceramic ones (Fig.16). She finished them with a varnish. Her work, she told me, was going well but mainly selling to North America and not so much within Morocco. For Moroccans it probably seemed a strange transgression to apply such female body decoration to plates while, for the outsider market, henna designs have a strong exotic message conveying a hint of Arab or North Africa. This young woman was an innovator.

In the photograph from the Aberystwyth display I was also showing the way that such bowls were used for eating fufu and soup and, furthermore, the way the form had migrated over to re-cycled metal (Fig.17).

I had visited Nesta Nala in KwaZulu Natal in 2000 and purchased an example of her work at that time along with some other smaller pieces, which demonstrate the highly refined development of the beer pot form that she and her family pioneered (Fig.21). In the exhibition Nala’s beer pot was shown alongside a burnished vessel by the South African potter, Ian Garrett (Fig.22). He had been much influenced by these forms and had written a dissertation on Nala’s work when he was a ceramics student at Pietermaritzburg.

From the visit in 2000 I already had an example of the work of Thembi Nala, Nesta Nala’s daughter but for Sankofa I commissioned a specific piece from Thembi with a design based on an AIDS narrative (Fig.23). When I had first seen her work I much preferred Nesta Nala’s work, which was always, as far as I am aware, based on very refined but decorative elements derived from early prototypes. I found the applied sprigs of narrative motifs less satisfactory aesthetically and I was suspicious of their very obvious ‘Zulu’ imagery in the scenes that I saw as being very clearly addressed to the outsider market. But, of course, it all was, and by 2005 I felt it was important to represent this development and in particular the widespread theme of AIDS imagery which was appearing on so much craftwork especially embroidery and beadwork.

In the art and sound installation Naming the Money (2004) the Zanzibar-born, British artist, Lubaina Himid used life-size cardboard figures of people representing different professions from her African homeland. Each had a small audio player attached at the back. As you approached a figure you could hear them whisper their name and something about themselves. The potter said: My name is Rashida They call me Sally I used to make pots for the whole village Now I make garden pots I am told they are much admired It can sum up neatly the plight of the potter, usually a woman, in many parts of Africa. It is very hard for her to acquire the understanding and insight into the wider world where her ceramics might circulate. Women have generally less access to basic education than men and especially so in relation to higher education. Contemporary African ceramics inevitably have to be driven by the marketplace in a way that is not the case in Europe or North America where leading ceramicists are often supported at least for part of their career and their income by studying and eventually teaching in institutes of further and higher education. This allows for a freedom to experiment, to travel, to study and to network that is much more difficult for most makers in many countries in Africa and, I would suggest, especially so for women. Sankofa was not an exhibition about women potters but inevitably, given the traditions of ceramics in Africa, women potters featured very strongly in the show. I would like to think it did justice to their amazing and still, much undervalued, work. Both versions of the exhibition attempted to convey some of the different contexts for contemporary ceramics in Africa through displays and supporting photographs. In Manchester the furniture and display cases made no effort to appear ‘African’ but asked the audience to draw parallels with different places where such works might be seen – from museum store to art exhibition and from kitchen table to drawing room display case. In Aberystwyth, a very much smaller space where everything had to be in fixed display cabinets there was more suggestion of colours, textures and material culture and we were able to convey a better sense of the fieldwork and process of collecting which reflected the subtitle for the exhibition – Ceramic Tales from Africa. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 1 Gary van Wyck ‘Convulsions of the Canon’ African Arts Autumn 1994, p.60. 2 A ceramics enthusiast, the main buyer, the architect Sidney Greenslade, was based in London and purchased early studio ceramics including work by Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada and, most notably, a fine collection of Michael Cardew slipware from Winchcombe. It was these works of pioneer studio pottery that formed the basis of the redevelopment of the ceramic collection at Aberystwyth after 1975. 3 For further discussion of this see Vincentelli, M. ‘Reflections on a Kabyle Pot: Algerian Women and the Decorative Tradition’ Journal of Design History, 1989, 2(2&3), pp.123-138. 4 The pottery has since been renamed the Ladi Kwali Pottery. 5 Tanya Harrod The Independent, 21 July 1989. 6 There are more examples of such black pottery in the World Museum, Liverpool. The major collections at Liverpool were made by Arnold Ridyard but in 1910 the new director of the museum asked him to collect ‘examples of arts and industries that were thought to be dying out, in particular the ‘primitive potter’s art’ (Annual Report 1911) see Tythacott, Louise (2001) 'From the ‘fetish’ to the ‘specimen’: the Ridyard African collection at the Liverpool Museum 1895-1916.' In: Collectors: expressions of self and other. London: Horniman Museum, pp. 157-179. See also Louise Tythacott The African Collection at Liverpool African Arts, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Summer, 1998), pp. 18-35+93-94. 7 I am grateful to Nii Noi Dowuono who worked as an advisor to the potteries at Kpando and put me in touch with the potters there. 8 At that time worth about £40. 9 Emma Poulter ‘The Real Thing? Souvenir objects in the West African collections in the Manchester Museum’ Journal of Material Culture 2011 16:265-283. 10 For a description of the production of pepper grinders see Marla Berns ‘Pottery Making in Bonakire, Ghana African Arts Spring 2007 pp 86-91. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

African Pottery, studio pottery and contemporary ceramics on display: Sankofa, Ceramic Tales from Africa • Issue 17 |