Interpreting Ceramics | issue 17 | 2016 Articles, Reviews |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Reflections on Fired – An Exhibition of South African Ceramics at Iziko Museumsby Esther Esymol, Curator Social History Collections, Iziko Museums of South Africa |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract

Introduction Fired – an Exhibition of South African Ceramics celebrated South Africa’s rich and diverse legacy of ceramic making. The exhibition showcased a selection of about two hundred ceramic works, including some of the earliest indigenous pottery made in South Africa, going back some two thousand years, through to work produced by contemporary South African ceramists. The works were drawn mainly from the Social History Collections department of Iziko Museums of South Africa.1 Design and curatorial approaches Fired was installed at the Castle within an evocative space with arched ceilings and columns, and presented in two large elongated chambers (Fig.1). Created in the late seventeenth century, the space was originally used as a Granary during the time of Dutch East India Company rule at the Cape.2 The design of the exhibition was approached with sensitivity towards the heritage aspects of the space and respect for the unique architectural features of the locale. Although it is one of the Castle’s most beautiful venues, the Granary has relatively limited floor space due to the many columns. This posed a challenge regarding the positioning of glass display cabinets required to exhibit ceramics safely. The exhibition designer worked sensitively around these limitations and created a visual balance between the display furniture and the architectural elements, positioning the display cases centrally, rather than placing them along the outer walls. Furthermore, the designer chose not to hide special architectural features such as old niches, staircases and doors, but opted to present the exhibition against the historical and textured backdrop provided by the original fabric of the building.3

The exhibition was produced with a modest budget. For example, resources for new, custom-built exhibition cases were not available. Existing display cases needed to be reutilized, some of which required minor adaptations such as the addition of glass shelves. A number of flat cases originally intended for the display of books or photographs, were adapted to display smaller ceramic items and flatware best suited to being viewed from above. Despite these constraints, Fired was undertaken with an enthusiastic and optimistic spirit. Very importantly, the exhibition provided Iziko with an opportunity to showcase ceramics from its amalgamated holdings in a single display dedicated solely to ceramic art, one of the first combined exhibitions in a single medium of this type to take place following the Iziko formation. In selecting items for Fired, the aesthetic qualities of the ceramic works were of uppermost importance. We wanted to show the beauty and diversity of the rich range of South African ceramics. As an institution that had evolved from a divided past, it was imperative to have a new and integrated approach towards the display and to move away from showing ceramics, especially rural ceramics, as objects of craft. All ceramic works were placed on an equal footing, no matter whether it was made in a rural or urban setting, by a named or unnamed artist. We approached the exhibition by selecting both historical and contemporary works, often displayed in juxtaposition or interspersed with each other. Ceramics made by both established and emerging ceramists were regarded as equally important. Works created by named ceramists, or those whose names had not been recorded, or whose work does not carry the name or mark of its creator, were viewed equally as appropriate for inclusion in the exhibition. Whether collected during fieldwork trips into rural areas, or purchased at urban sales auctions, we elected to focus selection around the beauty and meaning of the works, as well as the ceramists who created them, rather than drawing distinctions between works based on different collecting methodologies or collecting foci, or making a differentiation between ceramics as art or craft objects. If the name of a maker was not known, or had not been recorded in the museum records, the related exhibition texts and object labels made reference to the area where the work had originated, rather than mentioning an ethnic group as being the collective makers of the work. Although these works had been categorized in museum documentation records according to classification systems based on ethnic or linguistic groupings,4 we wanted to depart from the practice of displaying the works within these confines. We thereby took cognisance of the complexities around pronouncing works as originating from homogeneous cultural or ethnic groups. What is in a title? Why was the title Fired selected for this ceramics exhibition? We felt it highlighted the power of fire to transform malleable earth or clay into a hardened material called ceramic. The title furthermore resonated well with Iziko’s own transformation processes when the separate collections were brought together in 1998 through the formation of a new amalgamated museum group. Fire is also symbolic of inclusivity, in the sense that as a process it does not discriminate - whether a clay object was created by a female or male ceramist, whether it was made from different kinds of clay (i.e. earthenware, stoneware or porcelain), or made by various techniques (i.e. being built by hand, thrown on the potter’s wheel or cast from a mould) – all objects created from clay turn into ceramic once they have interacted with fire. We therefore felt that Fired was an all-inclusive, unifying name for our diverse collection of ceramics, simultaneously celebrating their integration into the Iziko group. History of the collection The respective pasts and collecting foci of the museums, which today make up the Iziko group, stand at the root of the present Iziko collection and have defined the kinds of ceramic work currently held within the institution. The collection was initially gathered at various Cape Town based museums over a period of more than a hundred years, through archaeological excavations, fieldwork trips, private donations, sponsorships, purchases from commercial galleries and at auction, or obtained directly from artists working with clay. For example, the South African Museum (SAM), which was established in 1825, but formally constituted in 1855, had a department of Ethnology which changed to Ethnography in 1982, and thereafter to African Studies & Anthropology. This department focussed on the study of southern African material culture. Ceramics, amongst other objects and practices, were collected by way of fieldwork in a quest to research and document indigenous craft objects. Since the 1970s a selection of ceramic vessels had been exhibited with other cultural objects and practices in the so-called ‘Ethnography Gallery’, at the SAM to portray the lifestyles and cultural practices of various indigenous groups. Body casts had been incorporated into these displays. At one point the cast of a female potter at work formed part of the exhibition in this gallery space.5 The former South African Cultural History Museum (SACHM), which was created in the 1960s as a history museum separate from the SAM, was largely perceived as holding European or colonial collections.6 Initially the SACHM's collection of ceramics comprised mainly European and Asian ceramics. The South African ceramics section started developing at a later stage in 1975, when a donation of early twentieth century studio pottery made by Cape Town based potter, Leta Hill (d.1973), was received. Then, from about 1984, the SACHM’s South African ceramics collection started growing more significantly to include works created at many of the major twentieth century production pottery studios in the country, as well as contemporary ceramics made by important individual ceramists from across South Africa. A room dedicated to the display of ceramics was opened in 1988 at the former SACHM building, today known as the Slave Lodge. The ceramics were displayed in an open storage formation and included works originating from all over the world. About two display cases were dedicated to South African studio ceramics. The work of emerging ceramists started entering the collection during the latter years of the existence of the SACHM and continued during the early years of Iziko when a special project called Bumba udongwe – Working with clay, was launched. This project took place between 1998 and 2002 when fieldwork trips were undertaken to townships around Cape Town to locate artists working with clay. The ceramists were interviewed, documentary photographs were taken and works were selected for a series of annual exhibitions in Cape Town. The exhibitions took the form of selling displays, and were held in the foyer of the administration building of the SACHM on Church Square in central Cape Town.7 During the 1960s Dr William Fehr (1892-1968), who assembled the Fehr Collection of paintings and decorative art objects, as well as art works on paper (on display at the Castle of Good Hope and Rust en Vreugd Museum respectively), incorporated stoneware vessels by prominent ceramist Esias Bosch (1923-2010) into his art collection. With the formation of Iziko Museums, all of these formerly separate collections were brought together within the newly created Social History Collections department, thereby amalgamating collections of ethnography and pre-colonial archaeology formerly held at the SAM, the collections of the SACHM, as well as that of the William Fehr Collection. The collections of the former South African National Gallery (SANG) entered the Iziko The above broad collections base provided a wide selection of ceramics for the Fired exhibition across the entire spectrum of ceramic production in South Africa. Exhibition themes An important aim of Fired was to share information about the development and history of South African ceramics production with a wide range of visitors and learners. Texts and images were utilized as a means to communicate information to the visiting public, especially those not necessarily familiar with South African ceramics history. Information texts written by members of a curatorial team9 were printed and attached to existing wall panels spanning one side of the gallery space. Images were also included, selected either from photographic resources in the museum’s archival holdings or from sets of images taken especially for the exhibition (Fig.2). These images were produced by Iziko's photographer, Carina Beyer, during visits to a number of Cape Town based ceramic studios, including those of Andile Dyalvane (b.1978), Hennie Meyer (b.1965), John Bauer (b.1978), Lisa Firer (b.1970) and Ellalou O’Meara (b.1944).

The information panels started off with an introduction and overview of various technical aspects related to pottery making. A timeline followed focusing on points of local relevance in the history of ceramics production, with some global developments included as historical reference points. Events mentioned included the most important ceramic finds at southern African archaeological sites, and the dates when the most well-known production potteries in south Africa were in operation. References were also made to accolades bestowed on some of South Africa’s best-known ceramists. Another feature of the exhibition was a DVD film which carried the following inserts:

The DVD film brought life to the exhibition by providing educational footage on various pottery making techniques used by ceramic artists working in both rural and urban areas of South Africa. It also complimented the works in the exhibition made by the ceramists who featured in the film. The information on the wall panels in Fired was arranged according to themes conveying important aspects of South African ceramics history, such as:

Although the ceramic work had been arranged throughout Fired to loosely follow the layout of the information panels, a strict chronology was not always adhered to. Historical and contemporary works were juxtaposed at times to illustrate enduring links and influences between the past and present. Sub-themes for individual display cases were developed to support the way in which particular objects were grouped. These sub-themes were Storage vessels; Vessels for drinking, serving and making beer; Inspired by ancestors; Of Khoesan origin; Lydenburg heads; Ceramic journeys; Production pottery; Designs on Africa; Studio ceramics; Forms in porcelain; Embodied earth; Contemporary ceramics. Storage vessels A selection of large storage containers were chosen to be the first objects on view upon entering the Fired exhibition. These hand-built and burnished vessels were made to hold food or liquids such as water and beer, and resonated with the storage function of the original grain cellar, for example a vessel made in 1962 by Sophie Gumede at Shongwe in KwaZulu-Natal and a vessel made by Maria Mulaudzi in 1976 in Limpopo, as well as a burnished beer vessel or nkho, which was made at Butha Buthe in Lesotho in 1962 by an unnamed ceramist. Vessels for drinking, serving and making beer To highlight various surface treatments and the decoration of ceramics, a number of vessels made for the making, drinking, and serving of beer were grouped together (Fig.3). Vessels used for storage or the brewing of beer were frequently not decorated, while vessels used for serving beer were usually embellished with decorative motifs. To illustrate these practices vessels were chosen from various areas in southern Africa, the earliest being beer serving vessels from the Flagstaff, Herschel and Mt. Frere areas in the Eastern Cape, respectively dating from 1907, 1932 and 1948. Juxtaposed with these earlier works were vessels by Alice Qga Nongebeza (1928-2012), dating from 2008 and made in the Port St. Johns region in the Eastern Cape. Also included were stemmed drinking cups made by unnamed South Sotho artists in Lesotho. Echoing this traditional pottery style but made within a contemporary context in an urban environment, were lidded stemmed cups produced in 1999 by Makgwase Lefata at Khayelitsha in Cape Town. Lefata utilized burnt-out light bulbs to burnish her works.

Most of the exhibited works were decorated with impressions of geometrical lines impressed into the soft clay surface prior to firing. Decoration was also applied to the surfaces of some of the vessels through the addition of shaped pellets of clay or amasumpa. This distinctive technique was often utilized for vessels made in the KwaZulu-Natal area, and may allude to a style of body patterning. Inspired by ancestors Inspired by ancestors celebrated the importance of the continued use of ceramics in cultural rituals and ceremonies, as well as the legacy of the knowledge transfer of pottery making within family groups. An arrangement of blackened vessels made in the KwaZulu-Natal area was used to illustrate the fact that the offering of beer in earthenware vessels continues to form an integral part of important cultural rituals, thus contributing to the survival of pottery making despite the availability of containers made of materials such as aluminium or plastic. The transfer of skills is another important aspect required for the survival of pottery making. Luckily members of the older generation have been teaching younger family members, such as in the case of the late Nesta Nala (1940-2005), who taught pottery making to her daughters and extended family members. Works made by members of the Nala family, such as Jabu Nala (1969-) and Thembi Nala (1973-) were included in this section of the exhibition (Fig.4).

It is also important to note that although the making of functional ceramic vessels in Africa is traditionally a woman’s role, ceramic making today is no longer an exclusively female activity. For example Clive Sithole (b.1971) (Fig.5) and S’bonelo Tau Luthuli (b.1981) are young men who work with clay in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal. They create elegant decorative vessels based on the shapes of traditional Zulu beer-drinking and serving vessels such as the ukhamba (spherical drinking vessel) and uphiso (necked vessel). Also honouring indigenous pottery making techniques and forms is Ian Garrett (b.1971) (Fig.6) who has closely studied the work of Nesta Nala. Garrett currently works in a rural area outside Swellendam in the Western Cape, where he creates finely burnished hand-built vessels meticulously decorated by way of either mussel-shell impressions or raised contours in the design.11

In Fired, works by these contemporary ceramists were juxtaposed with older works to illustrate how contemporary ceramists continue to draw inspiration from historical vessel forms. Many of the contemporary works, however, were not made for ceremonial purposes but were rather created as decorative vessels. These vessels fulfil modern needs and purposes, and are frequently bought by commercial galleries and international stores, and sought after by interior designers as unique décor objects.12 Of Khoesan origin Amongst the oldest objects exhibited in Fired, were vessels made by indigenous Khoekhoe herders.13 Of Khoesan origin showcased archaeological vessels found in the Western and Northern Cape at Blaauwbergstrand (Fig.7), Mossel Bay and Keimoes in the Gordonia area. These low-fired earthenware vessels were hand coiled by women and were typically created with thin walls, often shaped with pointed or conical bases for positioning in sandy soil. Perforated lugs often appear at the shoulders or necks of these vessels for the attachment of leather, twine or similar handles for carrying purposes. Some vessels are delicately decorated, others left plain.14 These vessels were designed to perfectly suit the nomadic lifestyle of the Khoekhoe people.

Lydenburg heads One of the seven iconic Lydenburg sculptural heads featured amongst the earliest ceramics exhibited in Fired. The Lydenburg heads are helmet-shaped earthenware objects found during the 1950s and 1960s at Lydenburg in the present day Mpumalanga province in South Africa. The heads are usually on display at the Iziko South African Museum but by special arrangement one of the smaller examples that combined both animal (aardvark) and human features, was temporarily included in the Fired exhibition at the Castle (Fig.8).

The heads have been dated to around 750 CE. Their special modelled features include cowrie-shaped eyes, wide mouths, raised bars across the forehead defining the hairline or representing scarification; incised bands hatched around the necks echo the decoration applied to domestic pottery found at the site. The precise use and meaning of these remarkable objects are not clear but they were possibly ritual objects used in initiation ceremonies. They reveal a complex aesthetic ability amongst early farming communities in southern Africa, at least a thousand years before European colonisation.15 Ceramic journeys Besides embracing the diversity of locally-made ceramics in Fired, Ceramic journeys also showed a small selection of ceramic objects of historical significance related to the trade in Asian ceramics. Trade networks between Africa and other parts of the world existed for thousands of years, as illustrated by the archaeological finds of Chinese Song (960 -1279CE) and Ming Dynasty (1368 -1644 CE) ceramics, discovered at important early trading sites such as Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. By 1200 CE Mapungubwe, at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers, was at the centre of a southern African trading empire. Porcelain from China, such as green-glazed celadon ware, as well as cloth and glass beads from India, were imported and exchanged for gold, ivory and hides. By 1270 CE Mapungubwe had been displaced by Great Zimbabwe as the most powerful trading state in the region.16 Years later, when the Dutch landed at the Cape in 1652 to set up a fortified refreshment station for the Dutch East India Company or VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), they brought with them European ceramics of the period and small amounts of Chinese porcelain. Official VOC shipments of export ceramics to the Cape began in 1666 with a small consignment of Iranian (Persian) ceramics. Subsequent shipments included both Persian and Japanese ceramics, followed by numerous consignments of Chinese porcelain beginning in 1678.17 Early on in the colonial period an attempt was made to produce European style domestic ceramics locally. The second commander in the service of the VOC at the Cape, Zacharias Wagenaer, wrote to Company officials in Batavia in 1663 asking them to send potters to the Cape ‘as he was much in need of pottery’. Following this request, the first European-type coarse earthenware, referred to as ‘VOC earthenware’, was produced at the Cape by immigrant European potters.18 Some historical ceramics of Asian origin were shown in Fired, for example blue and white porcelain dishes made at Arita in Japan. These dishes were decorated with the monogram of the VOC and made to be used by VOC officials at Company offices. Also included in the exhibition were fine polychrome enamelled Chinese ceramics decorated with the familiar setting of Table Bay, against the backdrop of Table Mountain, produced during the mid-eighteenth century.19 Links were made between these older works and contemporary South African ceramics, such as a small tile panel by Ellalou O’Meara (b.1944), delicately painted with a depiction of a historical scene of Table Bay and Table Mountain. O’Meara often draws inspiration from the designs and patterns of Asian trade wares for the decoration of her table wares. Also shown in Fired was one of a pair of large and impressive terracotta lion sculptures (Fig.9). These sculptures originally adorned the entrance gate to the Castle of Good Hope and date from the early 1700s. They were created in a style suggestive as being of South East Asian origin, though it is possible they were made at the Cape by Company officials or Asian masons and slaves. The original sculptures were removed from the Castle gate after they were damaged towards the end of the twentieth century. Today replicas meet visitors upon arrival at the Castle.20 It was deemed important to bring at least one of the original sculptures from storage into Fired, as it is one of the oldest clay sculptures dating from the early colonial period.

Production pottery The production of local ceramics on a commercial scale started quite late in South Africa. The reasons for this are linked to the fact that ceramics were imported from elsewhere over the course of many years, rather than having been produced on a significant scale locally. During the Dutch colonial period, for example, large numbers of Asian ceramics were imported to the Cape. After the second British Occupation in 1806 the importation of British ceramics dominated the South African market. It was only at the beginning of the twentieth century that a number of production potteries came into existence and started becoming commercially operational in the country. Amongst the earliest and best known South African production potteries was the Ceramics Studio (active 1925-1942), later called Linnware (active 1942-c.1962). This pottery was famously founded and run by a small group of women. They operated from the Olifantsfontein area situated between Johannesburg and Pretoria in the present day Gauteng province. A selection of work by this pottery was shown in Fired, as well as work by a number of other production potteries which were established during the course of the twentieth century, for example Globe Pottery, Dykor Ceramic Studio, Crescent Potteries, Hamburger’s Pottery, Drostdy Ware and Zaalberg Potterij (Fig.10). By the 1950s the local ceramics industry consisted of over forty potteries, mostly established in urban centres throughout South Africa. During the late 1950s, however, deregulation of government import tariffs and quotas, and ‘dumping’ of cheap ceramics from Japan and the USA resulted in the bankruptcy of many of these smaller potteries.21

Designs on Africa For the Designs on Africa display case, ceramic works were selected highlighting the strong influence of African designs on twentieth century South African ceramics (Fig.11). The aesthetics of geometric patterning, imagery of Africans, particularly figurative studies of women, and women dressed in traditional headgear and neck ornamentation, featured as popular design motifs, especially during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Kalahari Studio (active 1948-1973), viewed as the pre-eminent ceramic studio in South Africa during the 1950s, was one of the production potteries that frequently used African designs as decorative elements. Examples of their work were included in the Designs on Africa display case. The Studio was started by two Latvian immigrants, Alexander (Sacha) Klopcanovs (1912-1997) and his wife, Elma Vestman (1914-1991). Both were trained in the arts in Northern Europe during the late 1930s and early 1940s, and arrived in South Africa in the late 1940s. In 1948 they set up the Kalahari Studio in Johannesburg, relocating to Cape Town in 1950. Their work reflected a merging of Northern European Modernist design trends and philosophies, with indigenous South African imagery.22 Studio ceramics Work by some of South Africa’s best known studio potters was shown in the Studio Ceramics section of Fired.23 A number of these artists had been associated with the Anglo-Oriental studio pottery movement established by Bernard Leach (1887-1979) in England. This studio pottery movement first gained impetus in Britain when Leach returned from Japan in 1920 and established a pottery at St. Ives, Cornwall. His work was strongly influenced by Chinese, Korean, Japanese, as well as medieval English ceramics, hence the term Anglo-Oriental applied to the movement. South African ceramic production was strongly influenced by this movement, especially during the 1950s through to the 1970s when it became fashionable to use typically dark-coloured or neutral glazes, in combination with subtle brushwork decoration. In South Africa, early exponents of this movement were Esias Bosch (1923-2010), Hyme Rabinowitz (1920-2009), Andrew Walford (b.1942) and Tim Morris (1941-1990). Although ceramists still work in this style today, the overwhelming popularity of the tradition declined from the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards when a more colourful, eclectic and sculptural approach to South African ceramics was adopted.24 Works by a number of potteries referred to as Community Economic Development (CED) potteries,25 were also integrated into the Studio ceramics display case. Best-known amongst these potteries are Kolonyama and Thaba Bosigo of Lesotho, Mantenga Crafts of Swaziland, and the Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre of KwaZulu-Natal (Fig.12).

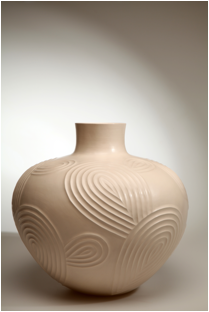

Rorke’s Drift were probably the most interesting of these potteries as a very special and unique hybrid style of ceramics developed here from the 1960s onwards. The artists not only drew inspiration from indigenous Zulu and Sotho material culture, but were also influenced by twentieth century modernist Scandinavian design trends by way of various teachers associated with the Art and Craft Centre.26 The male ceramists at Rorke’s Drift, for example Gordon Mbatha (b.1948), Joel Sibisi (b.1945) and Ephraim Ziqubu (b.1948), focussed on wheel-thrown ware, while the women ceramists, such as Dinah Molefe (b.1918 or 1927) and her relatives, created hand-built vessels by way of coiling. The division of work along gendered lines - men throwing, women coiling - resulted in two distinct styles of ceramic work being produced.27 The work of leading South African women studio potters, such as Marietjie van der Merwe (1935-1992), was also incorporated into the Studio Ceramics display. Van der Merwe played an important role in laying the foundations of Modernist approaches to South African studio ceramics and excelled in working with porcelain. Trained in the USA and Scandinavia, she was exposed to formal design elements prevalent during the 1950s and 1960s. One of her earliest porcelain works was included in Fired, namely part of a tea service with an orange-yellowish glaze colour, made in 1962 when she studied in the USA. Van der Merwe also played a leading role at Rorke’s Drift as consultant and studio advisor, from 1971 until her death in 1992. She introduced the use of stoneware clay there and assisted the artists in resolving various technical difficulties by improving the glazes and slips that were used.28 Forms in porcelain The arcades of the Granary are divided into two spacious chambers. Following the Studio ceramics display, the exhibition moved into the second chamber. In this section, Forms in porcelain showcased a collection of works by studio ceramists who work in porcelain as their preferred medium of expression. Fine vessels by Christina Bryer (b.1950), Lisa Firer (b.1970), Katherine Glenday (b.1960), Hennie Meyer (b.1965), John Newdigate (b.1968) and Wiebke von Bismarck (b.1941) were shown to celebrate the delicacy of works created in porcelain. The work of John Bauer (b.1978) was also included in this section with examples of his signature style porcelain bowls. These bowls are multi-layered and intricately embellished on both the interior and exterior with traces of ancient carvings and textiles, imprints of coins and engravings, as well as pieces of crochet. Slip-cast vessels made from found objects such as knitted caps were also exhibited to illustrate the versatile range of Bauer's porcelain creations (Fig.13).

Embodied earth Vessels and sculptures resonant with the shape of the human body were presented under the theme Embodied earth. This group of works featured sculptural vessels by Noria Mabasa (b.1938), who is a Venda ceramist from the Limpopo province of South Africa. Her ceramics are typically decorated in red ochre and graphite, a colour combination similar to that of the traditional works made in the same area. The contemporary Mabasa works were juxtaposed with traditional domestic pottery made by unnamed Venda artists. One such work is a spouted beer vessel or mvuvhelo made in 1940 in present day Thohoyandou in Limpopo (Fig.14).

Ceramics by Cape Town based contemporary ceramists such as Ralph Johnson (b.1943) and Louise Gelderblom (b.1964) also formed part of the Embodied earth display. Johnson’s large stoneware vessel was chosen because of its powerful form and richly textured red-slipped surface, which aesthetically complimented the red-ochred wares made in the northern parts of the country. Gelderblom's tall ovoid floor vase has curved lines and rounded features which are reminiscent of the human shape. Contemporary ceramics Fired featured ceramic works by a number of contemporary South African ceramists. These works were arranged throughout the gallery space as key pieces in tall stand alone glass display cases, for example Laura du Toit’s (b.1954) red-glazed vessel titled Sun spots. This vessel was selected as the signature work for all branding material related to the marketing of the Fired exhibition, as it expressed the warmth, colour and intensity of the firing process (Fig.15).

Another important contemporary work was a tall hand-built vessel by Andile Dyalvane (b.1978), one from a series called Views from the Studio and made at Dyalvane’s former Woodstock based studio in Cape Town during 2011. The intricately carved surface of this work portrays urban scenes as observed from the ceramist's studio, as well as imagery representing important cultural aspects close to the ceramist’s heart, such as music and the importance of cattle. The highly decorative surface treatment of this vessel represents Dyalvane's signature style which involves cutting the damp clay surface, a practice similar to scarification in traditional societies. Various contemporary ceramists prefer working in a quiet, minimalist and abstract style, as illustrated by a collection of wall plates created by Clementina van der Walt (b.1952), who works from Woodstock in Cape Town. Van der Walt’s plates carry brightly glazed colour blocks in compositions of squares, circles and rectangles applied on matt surfaces in abstract fashion. Work by one of South Africa’s internationally known ceramists, Hylton Nel (b.1941), also featured in Fired. Nel’s pair of quirky ceramic parrot figures are holding flowers in their beaks. They were displayed together with a pair of green-glazed Chinese parrots to illustrate the strong links that Nel has with historical ceramics, especially of Chinese and English (Staffordshire) origin (Fig.16).

Contemporary South African ceramics also maintain a major connection with the African landscape - its natural surroundings, vivid colours, rich textures, and abundant animal and bird life. The Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio (active since 1985), for example, has become famous for its exuberant creations which strongly feature African design elements. Ardmore typically transforms utilitarian shapes into fanciful, brightly coloured works enhanced by figurative work. A number of works by Ardmore were included in Fired, ranging from a pair of tall candlesticks embellished with elephants and lions, a baboon-shaped lidded vessel, a small giraffe bowl (Fig.17), to a fish bowl and a female figure carrying a baby on her back.

These ceramics all celebrated the fact that contemporary South African ceramics have been inspired by a wide range of sources, both historical and modern. South African ceramists are today free to work across cultural and artistic boundaries. Art has merged with craft and a multitude of technical innovations are being used to create new forms.29 Contemporary South African ceramics are typically eclectic in style with a maturity and confidence comfortably accommodating the rich imaginations of the men and women who have a passion for working in clay. Closing remarks Fired was very well received when it opened in February 2012. Various local newspapers provided positive coverage and reviews of the exhibition, and scholarly critiques appeared in international publications.30 Fired received the Western Cape government’s annual award for the Best New Museum Project in the year 2012/2013. The exhibition also inspired a new range of South African commemorative postage stamps, featuring a selection of ceramic vessels from the collection of Iziko Museums. This stamp series was launched in Cape Town on 13 November 2014. A remaining challenge for the Fired exhibition is the publication of a scholarly catalogue. Perrill refers to the need of a catalogue for Fired in her African Arts exhibition review31 in which she commented on two 2012 South African ceramic exhibitions, the one being Iziko’s Fired at the Castle, the other All Fired Up, a temporary exhibition which was presented at the Durban Art Gallery.32 Fired has been one of a few semi-permanent exhibitions in South Africa dedicated to the art of South African ceramics. The exhibition played a relevant role by providing visitors with an overview of the development of South African ceramics through history. During 2014 when Cape Town was the Design Capital of the World, Fired continued to provide an important platform through which contemporary ceramic work was showcased. The exhibition was temporarily closed in January 2015 to allow for renovations at the Castle of Good Hope, but is due to reopen in early 2016. The Social History Collections department of Iziko Museums has steadily continued to develop its contemporary South African ceramics collection with the addition of new ceramic works. The most recent acquisitions include works by Nico Masemolo (1985-2015), Hylton Nel (b.1941), Lisa Ringwood (b.1968), Nicolene Swanepoel (1962-2016) and S’bonelo Tau Luthuli (b.1981). These ceramics are to be incorporated into Fired updating the display once it reopens. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes 2 The Castle is the oldest existing colonial building in South Africa. It was built between 1666 and 1679, and served as headquarters for the Dutch East India Company or VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) at the Cape of Good Hope. 3 Exhibition designer and independent consultant Genneth Lyn is acknowledged for her sensitive approach towards the space and her invaluable contribution towards the layout and design of the exhibition. 4 Patricia Davison, Material Culture, Context and Meaning, A Critical Investigation of Museum Practice, with Particular Reference to the South African Museum, Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, March 1991, pp.104, 109-110. 5 Davison, Material Culture, Context and Meaning, pp.110, 128. It is to be noted that by 2013 all body casts had been removed from the ethnography gallery. 6 Lalou Meltzer, 'Foreword in the updated edition', Martin Legassick and Ciraj Rassool, Skeletons in the Cupboard, South African Museums and the trade in human remains, 1907-1917, Iziko Museums of South Africa, 2015. 7 Esther Esmyol, ‘A spirit of sharing, Bumba udongwe – Working with clay’, National Ceramics Quarterly, no.50, Summer 1999, pp.30-31. Esther Esmyol, ‘Bumba udongwe – Working with clay’, National Ceramics Quarterly, no.54, Summer 2000, pp.18-20. Esther Esmyol, ‘Bumba udongwe – Working with clay’, National Ceramics Quarterly, no.62, Summer 2002, pp.15-19. It is to be noted that the building which formerly housed the Bumba udongwe - Working with Clay exhibitions, today serves as storage facility for the reserve collections in the Iziko Social History Collections department. 8 Emma Bedford (editor), A Decade of Democracy, South African Art 1994-2004, From the Permanent Collection of Iziko: South African National Gallery, Double Storey Books, 2004. 9 Fired was curated by Esther Esmyol of Iziko Museums together with a curatorial team comprising current and past Iziko members, namely Dr Patricia Davison, Lindsay Hooper, Lalou Meltzer and Dr Gerald Klinghardt. Dr Davidson is especially acknowledged for her contribution towards the writing of exhibition texts and the naming of exhibition themes, and Dr Kinghardt for the creation of the timeline. The contribution and advice of Wendy Gers is also acknowledged, especially for her text on South African production potteries. Ms Gers is affiliated with the International Ceramics Research Laboratory as Coordinator/Ecole Nationale Supérieure d'Arts (ENSA) Limoges, France, a Research Associate with the University of Johannesburg, and a Lecturer at the Ecole Supérieure d'Arts et du Design de Valenciennes, France. She curated the 2014 Taiwan Ceramics Biennale. 10 The Earth is Watching Us was an exhibition held at the Gold of Africa Barbier Mueller Museum in Cape Town between 3 February and 31 March 2011. The exhibition was curated by Julia Meintjes and the photography for the film was done by Rauri Alcock. 11 Esther Esmyol, ‘Fired’, National Ceramics Quarterly, no.101, Spring 2012, p.25. 12 Elizabeth Perrill, Zulu Pottery, Noordhoek, Print Matters, 2012, pp.81-82. 13 The term Khoekhoe refers collectively to groups of indigenous herding people who spoke one of a number of related Khoekhoe languages, with San referring to hunter-gatherers. Khoe-San is used as an inclusive term for indigenous southern African hunter-gatherers and herders. 14 Ibid. 15 Ibid. The Lydenburg heads are on loan to Iziko from the University of Cape Town (UCT). 16 Ibid. 17 Jane Klose, Identifying Ceramics, An introduction to the Analysis and Interpretation of Ceramics Excavated from 17th to 20th century Archaeological Sites and Shipwrecks in the South-western Cape, 2nd edition, Historical Archaeology Research Group, University of Cape Town, HARG Handbook no. 1, 2007, p.27. 18 Klose, Identifying Ceramics, p.27. 19 Esmyol, ‘Fired’, p.22. 20 Esmyol, ‘Fired’, p.22. 21 Information obtained from text supplied by Wendy Gers for the information panel in Fired on South African production potteries. Gers defines a production pottery as a workshop or small factory that produces set lines of work. The emphasis is on efficient high-output rather than unique or original wares. Despite this, the pottery was often original and of a high quality. 22 Wendy A Gers, South African Studio Ceramics, c.1950s: the Kalahari Studio, Drostdy Ware and Crescent Potteries, Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Art, Centre for Visual Art, Faculty of Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, February 2000, pp.15, 25, 27-29. 23 As per text written for the Fired information panels, studio potters are defined as philosophically or stylistically associated with the Anglo-Oriental tradition of Bernard Leach (1887-1979), Shoji Hamada (1894-1978) and Michael Cardew (1901-1983). Some studio potters operate alone, while others work in small collaborative studios. They generally produced unique items or small series, usually with all stages of manufacture carried out by one individual. 24 Esmyol, ‘Fired’, p.25. 25 As per text supplied by Wendy Gers for the Fired information panels. Community Economic Development (CED) potteries were established in South African neighbouring states and former homelands. These potteries were initiated by local and international NGO's, humanitarian organisations and churches. They aimed to develop skills and jobs among rural communities. Several of these potteries took an anti-apartheid stance, including Rorke's Drift. Some of South Africa's most important black potters are associated with these potteries. 26 Ian Calder, 'The inception of Rorke's Drift Pottery Workshop: tradition and innovation', transcript of a paper read at the Annual Conference of the South African Association of Art Historians in Pietermaritzburg, 1999, www.artworx.org/za/calder.htm. 27 Penny Le Roux, ‘Rorke’s Drift Pottery’, Ubumba, Aspects of Indigenous Ceramics in KwaZulu-Natal, Albany Print, 1998, p.86. 28 Lara Du Plessis, Marietjie van der Merwe: Ceramics 1960-1988, Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Art in Fine Arts, Centre for Visual Art, School of Literary Study, Media and Creative Arts, University of KwaZulu-Natal: Pietermaritzburg, December 2007, pp.4, 36, 66, 68, 70-73, 77. 29 Esmyol, ‘Fired’, p.25. 30 Elizabeth Perrill, ‘Exhibition Review’, African Arts, vol.46, no.1, Spring 2013, pp.82-84. 31 Perrill, ‘Exhibition Review’, p.84. 32All Fired Up, Conversations between Kiln and Collection, an exhibition which took place between 2 March and 24 April 2012. End note: This article is based on a presentation made at the 16th ACASA Triennial Symposium on African Art held at the Brooklyn Museum in New York during March 2014. Gary van Wyk and the ACASA Symposium Planning Committee are thanked for the Scholar Travel Grant which was bestowed on the author. Wieke van Delen, formerly of Iziko, is acknowledged for her advice and proof reading of the initial version of this article. Elizabeth Perrill of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, USA, is acknowledged for her editorial input and mediation with the editors of Interpreting Ceramics. Kate Wilson Acting Editor of Interpreting Ceramics is thanked for her editorial comments, and Interpreting Ceramics for making this publication possible. Please note that the Fired exhibition has reopened in March 2016 in the Granary at the Castle of Good Hope. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

||||||||||||||||||||

Reflections on Fired – An Exhibition of South African Ceramics • Issue 17 |