Interpreting Ceramics | issue 17 | 2016 Articles, Reviews |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Making of National Ceramics Exhibitions of the Craft Potters Association of Nigeria (CPAN): An Historical and Critical Perspectiveby Ozioma Onuzulike |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Abstract

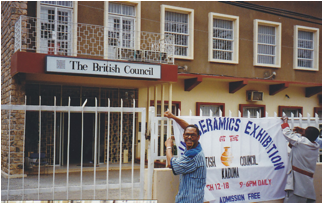

Introduction In February 1996, the first national exhibition of contemporary ceramics in Nigeria was held at the British Council Hall in Kaduna, Northern Nigeria.1 It was organised by the Ceramic Resource Centre Working Party, a collective made up of Joy Voisey, Tony Ogogo, Ben Drew and Margaret Mama (Fig.1). Voisey and Drew are British Nationals who had worked in Northern Nigeria in the early 1980s as arts and crafts teachers under the British Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) scheme. During their service term, they encountered the difficulties faced by Nigerian ceramics students and professionals in sourcing materials and equipment, as well as in making and showing their works. In Voisey’s own words, 'We [Voisey and Drew] were alarmed at the inability of ceramics graduates to start up small businesses and, despite an abundance of raw materials, Nigeria’s reliance on imported wares'.2

Earlier in 1991, Voisey and Drew had sent out questionnaires to Nigerian ceramics practitioners, teachers and students seeking to understand their pressing needs in general. The research showed that the 'fundamental needs … were a communication network, a central ceramic resource centre and a venue in which to show and sell work'.3 In the course of their consultations with the Nigerian ceramics community, Voisey and Drew undertook several trips to Nigeria, 'discussing the viability of starting a ceramics material resource centre'.4They also facilitated a Commonwealth Foundation Grant, which enabled two Nigerian ceramics graduates, Ayuba Gadzama and Umar Sullayman, to undergo further training in the UK. Gadzama undertook studies in ceramic workshop techniques and Sullayman in industrial ceramics.5 Members of the Ceramics Resource Working Party (who also addressed themselves as members of the Ceramic Voice6) met in 1995 and thought through the idea of organising the Nigerian potters with the aim of showing their work, sharing technical ideas and working towards the establishment of a national resource centre for the easy procurement of materials and equipment. The exhibition materialised with the support of the British Council in February 1996.

This paper reflects on the history of this exhibition model in Nigeria and how it grew to be sustained as standard during CPAN’s active years, especially from 1996 to 2006. Additionally, this paper looks beyond the physical display, offering insights into the manner in which the works shown in the CPAN national exhibitions reveal the development of some strands in contemporary Nigerian ceramic art. It proposes these as important exhibition themes that were never highlighted but rather glossed over by the Anglian-inspired model introduced by Joy Voisey and sustained principally by Ibukunoluwa Ayoola. As the formation of the Craft Potters Association of Nigeria resulted out of the need for cooperation among potters in surmounting the technical problems weighing down the development of modern ceramics in the country, a brief historical account of the roots of the problems is first provided. This historical contextualization will ensure readers possess the background to appreciate the major concerns of this paper. Such a historical account also provides useful insights into the making of the early ceramic art modernism in Nigeria.7 Background History of Modern and Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria The technical difficulties that characterised modern and contemporary Nigerian ceramics can be traced to colonial times. Problems appear to have resulted largely from inadequate teaching methods and limitations of technological transfer through the use of imported machinery, equipment and materials (particularly glazes) by agents of the British colonial government. The challenges faced by local contemporary ceramists are also traceable to the political economy that gave rise to the British industrial schemes in the country, especially following the years after the Second World War. The following examples will suffice to illustrate the above observations. The first recorded colonial pottery scheme in British West Africa was a workshop set up in Ibadan, southern Nigeria, in about 1904 by a colonial officer called D. Roberts.8 He constructed kilns from local clays but machinery (including potter’s wheels and lathe machines) and other essential materials such as glazes and Plaster of Paris (for mould making) were imported. The products of the Ibadan workshop also lacked local content in terms of form and competed with imported mass-produced factory wares.9 Apparently, there was a lack of technical support for the young men and women that Roberts trained to carry on with production by the time he left Ibadan in about 1912. They could not, for example, produce their own glazes, nor did they understand the complexities of high temperature kiln firing. So, in the absence of sustainable knowledge transfer (or, in fact, a total lack of it) the pottery was closed down and the equipment vandalised.10 After D. Robert’s pottery scheme, came the pottery experiments by Kenneth Murray (a colonial education officer), using locally available materials. This scheme was implemented during Murray’s teaching career in the Southern Provinces of Nigeria from 1929 to 1939. After his apprenticeship with the influential British potter Bernard Leach in 1929, Murray had tried to improve the work of traditional potters by introducing the potter’s wheel and glazes. Although he did not have enough time to conclude his pottery experiments, he never taught pottery, per se, to his students. These students had received some formal education in basic science and were thus better equipped to understand the science of glazes and high temperature firing than the traditional women potters. Emphasizing the distinction between these two groups, Murray rather taught his students to prepare clay, produce clay sculptures in relief panels and in-the-round and build simple up-draught kilns to fire them.11 The terracotta sculptures that resulted formed part of the historic exhibition of the works of his five special students (Uthman Ibrahim, Ben C. Enwonwu, Christopher C. Ibeto, D.L.K. Nachy and A.P. Umana) at the Zwemmer Gallery, London 1937.12 I have argued elsewhere that Kenneth Murray introduced in Nigeria, through the agency of colonial education of the 1930s, the Eurocentric notions of pottery as ‘handwork’ and terracotta sculpture as ‘art’, thereby defining the direction which modern creative expressions in clay were to take in the country throughout the twentieth century.13 No further significant development took place in the Nigerian ceramics scene until April 1950 when a colonial pottery training centre was set up in Okigwe, south-east Nigeria by Victor Gregory, a colonial pottery officer hired from Britain by the Federal Department of Commerce and Industries. At Okigwe, trainees were taken in batches from different pottery producing communities in the region. Like the earlier pottery scheme at Ibadan, however, the Okigwe Pottery Training Centre used imported glazes and produced alien ceramic forms,14 making it impossible for those who trained there to compete with the influx of cheap imported ceramic wares from Europe and Asia. A similar fate was suffered by the Pottery Training Centre Ado-Ekiti, (opened in 1952 to serve the South-West region), under another colonial pottery Officer, Andrew Gregory.15 Under the famous British colonial Senior Pottery Officer, Michael Cardew, from 1952 to 1965, the Pottery Training Centre, Abuja (now Suleja in Niger State, Northern Nigeria) succeeded remarkably in producing wares that were inspired by Nigerian native pottery forms and decorations, such as those of the Gwari, Ido, Ushafa and Tatiko.16 Even when European forms were introduced (at the Abuja Pottery, for example) they were decorated largely in the traditional pottery spirit using sensitive line work that sometimes defined zoomorphic motifs.17 Although heavy machinery was imported from Britain for processing basic raw materials, Cardew’s use of glazes created from locally available minerals, collected from around Abuja and Jos, was on par with his emphasis on local decorative motifs.18 Unfortunately, almost all of the trainees chosen by Cardew (including the famous Nigerian female potter, Ladi Kwali) were illiterate and could not be effectively trained in the science of glaze production. Danlami Aliyu19 put this more succinctly in his critique of the Abuja Pottery Centre under Cardew, stating:

This criticism by Aliyu was almost like saying that Cardew’s project was a failure, a situation that fired Michael OBrien’s determination to return to Nigeria to continue from where Cardew, his master, had stopped.21 Michael OBrien and the Challenge of Technical Difficulties in Modern Nigerian Ceramics Production Following Michael Cardew’s retirement from the Abuja Pottery Training Centre in 1965, Michael OBrien,22 an art graduate from the Farnham School of Art, was appointed to run the Abuja Pottery. OBrien had arrived in Abuja in 1963 to study under Cardew after teaching at Leicestershire for seven years and taking pottery lessons on his own. At the end of six months, he was offered a teaching appointment at the Abuja Secondary School, just opposite the pottery centre.23 Drafted into the PTC as Pottery Officer when Cardew retired in 1965, OBrien was mandated to make the pottery, which had relied heavily on government subvention, to become self-sustaining, in line with the advice of some American economists, otherwise the facility would be closed down. To achieve this mandate, OBrien re-designed Cardew’s wood kiln, constructing a bigger one. In his new kiln, he thoughtfully introduced a recuperator to achieve greater efficiency in the use of fuel and firing time.24 Previously, the old kiln was fired for between thirty-five to forty hours, but OBrien’s new kiln fired for only twenty hours using less firewood to gain twice the previous output. He appointed foremen to oversee the workers for increased productivity and organised shows in Kaduna and Ibadan, which helped to ensure that Nigerians would buy the Centre’s products and that sales did not lie only with the expatriates.25 Michael OBrien left the pottery and returned to England in 1972. The PTC, Abuja managed to remain alive until the 1980s when the IMF-induced Austerity Measure and Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) of the government, along with bad management, official corruption and technical problems, disabled the scheme totally. However, shortly after Danlami’s thesis was published as a special issue of Pottery Quarterly in 1979, OBrien was appointed to teach Ceramics at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, in Northern Nigeria. He saw this appointment as an opportunity to ‘complete’ Cardew’s work in West Africa. His task became to simplify the complexities of glazed pottery production. So, OBrien decided to take his students out to identify local materials from the immediate environment for use in compounding glazes. He discarded Cardew’s use of molecular calculations in the making of glazes because the pure scientific method meant that materials had to be taken to laboratories overseas for testing. In its place, he adopted what he calls the 'Hamada Method'.26 OBrien resigned from the University in 1985 when his proposal to have students do a five-year degree course (as opposed to the existing three years) was rejected. He felt that his purpose was not being achieved in the University setting because he considered three years to be inadequate for training specialising ceramics students to be able to build their own kilns, produce their own glazes and stains and construct their own wheels, which was the only way out of the technological and economic situations in the country. In the same year, OBrien banded together with Danlami Aliyu and three other people to start the Maraba Pottery near Kaduna. Earlier, in 1983, while he was still teaching at ABU, Zaria, O’Brien had helped to set up the Jacaranda Pottery for Margaret Mama and it was run with the help of OBrien’s outstanding students, as well as some staff of the moribund Abuja Pottery Centre and the Jos Museum Pottery, including Clement Kofi Athey. During his intensive work at Maraba Pottery with Danlami Aliyu from 1985 to 1987, the pottery was to become OBrien’s demonstrative programme in his quest to simplify modern ceramics production technology in Nigeria. At Maraba, workshops and other houses were built with mud bricks and thatched roofs in a similar fashion to Cardew’s at Abuja. Parts of the wood-burning kiln were constructed cheaply with mud bricks. No machinery was used. At the beginning, there was only a sieve and a kick wheel to work with! Glazes were made using granite dust collected from quarries, clay dug from around the vicinity, and wood ash generated from the kiln’s fire boxes. The kiln ran efficiently and the pottery made a profit and a good name for itself. This encouraged other independent potters to set up potteries, often with the technical and financial assistance of OBrien.27 This was how new potteries working in the Cardew spirit emerged in Northern Nigeria from the 1980s, especially the Al Habib Pottery owned by Danlami Aliyu (who left Maraba Pottery in the hands of his younger brother, Umaru Aliyu, to set up his own pottery in Minna) and Bwari Pottery (which was set up by Stephen Mhya in partnership with Michael OBrien) later in 1998.28 Towards a Ceramics Resource Working Party for Nigeria: Joy Voisey, Ben Drew, Tony Ogogo and Margaret Mama From the narrative above, it can be seen that by 1984 when Joy Voisey and Ben Drew came to Nigeria from England as volunteer teachers under the British Voluntary Overseas Service (VSO), Nigerian ceramics was in a period of crisis as a result of years of technical difficulties, especially in the areas of procuring pottery machinery and processing raw materials. This period was also the beginning of a major revival under the British pottery teacher Michael OBrien, especially in Northern Nigeria, which has remained the major centre of studio pottery production since Cardew’s remarkable work at Abuja.29 Voisey had trained as a ceramics teacher at Cambridge University (1966-69) while Drew was born in Nigeria of British parents but was educated and studied ceramics in the UK. From 1984 to 1988, under the Introductory Technology Programme of the Nigerian government, they both worked as arts and crafts teachers at the Bama Technical College, a teacher-training institution in Bama, Bornu State, Northern Nigeria. It was during the period of their work at Bama that they found their students could not process ceramic raw materials and did not have the training or facilities to fire their works. The situation inspired them, apparently in the VSO spirit, to contribute to the development of contemporary Nigerian ceramics. They built a kiln for the school in which the students’ clay models were fired, as well as another for the museum in Maiduguri where a ceramics graduate from the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria was employed but had nowhere to fire his works.30 Unfortunately, both Drew and Voisey had limited technical knowledge of making glazes out of local raw materials and even of kiln building and firing. Their initial attempts at firing the kilns they built met with failures. Their frustrations in having to import glazes from Britain, the technical difficulties they encountered in firing their brick kilns, and the realisation that there was a scarcity of technical ceramics information in the country, fuelled their determination to help address the situation.31 Voisey and Drew began by publishing the Ceramic Voice newsletter in October 1993 in which simple but crucial technical information was disseminated. In Issue One, they also communicated their dream for setting up a Ceramics Resource Centre in Nigeria to cater for tools and materials supply, demonstration workshops and exhibition spaces. To achieve their goal, they sought collaborations with like-minded individuals and found them in Tony Ogogo and Margaret Mama. This was how four of them banded into what they called the Ceramics Resource Centre Working Party. Voisey, Drew, Ogogo and Mama worked closely from 1995 to organise a weeklong exhibition of contemporary ceramics in Nigeria as a starting point for dialogue among individual potters and potteries across the country. This was realised successfully in February 1996. At the end of the exhibition and discussions, a national body for Nigerian ceramists was formed and modelled after the Craft Potters Association of Great Britain. It was called Craft Potters Association of Nigeria (CPAN). The exhibition itself, which was mounted by Joy Voisey, was modelled after the display techniques of the UK-based East Anglian Potters Association in which Voisey was (and remains) a committed member. Her exhibition strategy was to become the standard for subsequent CPAN annual shows. The Craft Potters Association of Nigeria and the Making of Annual National Exhibitions The inaugural exhibition of contemporary Nigerian Ceramics organised by members of the Ceramics Resource Centre Working Party in February 1-7, 1996 at the British Council Hall in Kaduna (Fig.3) was the first national ceramics exhibition of its kind in the country.

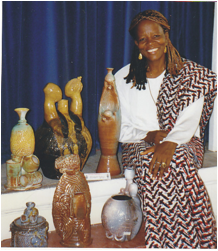

In mounting the main exhibition, Joy Voisey used the display strategy by which works belonging to each participant were grouped together, as in a trade fair, with the nametag of the exhibitor placed in a strategic location somewhere around each exhibit. This mode was sustained in all of CPAN’s shows (Fig.4).

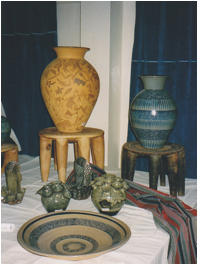

In addition to the use of box-like props on tables, Margaret Mama of the Jacaranda Pottery introduced in her stands the use of carved wooden stools, each of which had been designed with six tusk-like feet by local carvers. The stools were of varying heights and carried Jacaranda’s large decorative pots (Fig.9). This collaborative display strategy helped to domesticate in a Nigerian sense the Anglian model upon which Voisey constructed her exhibition format. The collaboration brought extra interest to the display, suggesting ways that a potential buyer might display the work (pots and sculptures) in a public or private space.

The Kaduna National Exhibition of February 1996 became the model display strategy of the annual CPAN exhibition throughout the active years of the Association, especially between 1996 and 2006. Added to this from 2001 was the adornment of the walls of the exhibition spaces with enlarged photographs of individual CPAN members with their works (Figs.10 and 11). This strategy introduced a sense of history to subsequent CPAN exhibitions, showing both exhibitors and their exhibits even when they failed to attend in person (Fig.12). The exhibition model introduced by Joy Voisey remained respected and unchallenged throughout the period under review.

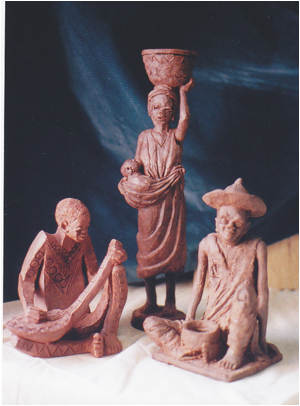

A critical look at many of the works included in the annual CPAN exhibitions shows that there is a great deal of information that can be read from these objects, especially regarding the manner by which individual potters and potteries negotiated their engagement with traditional and modern forms and techniques in the face of technical difficulties. A broad stylistic trend in the works shown in the decade under review appears to be that while potteries (such as Jacaranda, Dajo, Al Habib and Bwari) produced traditional table wares and decorative pots in the fashion of the famous Abuja Pottery Centre, many of the academically trained ceramic artists who came from the universities and polytechnics made work in the sculptural tradition reminiscent of the Kenneth Murray pupils of the 1930s.

The exhibitions also show that through their links with Michael OBrien (Michael Cardew’s successor at the Abuja Pottery Centre), Jacaranda, Al Habib and Bwari potteries that Cardew’s legacy in Nigeria has been preserved (Fig.16). This is especially visible in the manner by which the potteries have drawn from traditional pottery forms and decorations, as the Abuja Pottery Centre did under Cardew. It was, however, not the intention of the CPAN exhibition curators to highlight these developments and historical connections.

Conclusion Of late, there have been important exhibitions and publications devoted to the examination of what have been called ‘alternative modernities’ in the works of contemporary African ‘fine’ artists. But what happens to alternative modernities in African pottery and ceramic art? As shown here through the Nigerian example, much has happened in the development of modern ceramics,34 but these transformations in modernities have never been highlighted by any exhibitions. For example, no exhibition has paid attention to the modernist ceramic art that evolved through the work of colonial art teachers and potters in colonial and postcolonial Nigeria - especially Kenneth Murray (from 1929-1939), Michael Cardew (from 1952-1965) and Michael OBrien (1965 to date). While the landmark exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery in London in 1937 of the works of Murray’s students showed a line of early modernist ceramic sculptures that influenced much of emergent expressions by academically trained artists in the remaining part of the twentieth century and beyond, the connection between Murray’s pedagogy and contemporary Nigerian ceramic art has not been the subject of any exhibition. Similarly, the work of Michael Cardew and Ladi Kwali, at the famous Abuja Pottery Centre, form important links with similar modernist expressions in Nigeria’s postcolonial potteries (such as the Jacaranda, Maraba and Bwari potteries), and in a number of Nigerian universities and polytechnics, especially those located in Yaba, Zaria, Nsukka and Ife. But these developments have never been highlighted in any important exhibition. The ways in which Nigerian ceramics artists are moving beyond this modernist phase, as exemplified in the ceramic sculptures and installations of Chris Echeta, Ato Arinze, Ozioma Onuzulike, Nnenna Okore and Ngozi Omeje, lend the subject even more historical significance. I argue for exhibitions along such thematic lines that transcend the display or curatorial model instituted by Joy Voisey and sustained by Ibukunoluwa Ayoola which attempt to narrate and illustrate important aspects of the history of modernity and modernization in Nigerian ceramic art. The discourse of global modernism remains incomplete without exhibitions and publications that illuminate this important art historical theme in modern and contemporary African ceramic art. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next Notes

2 See Joy Voisey, ‘A Celebration of Ceramics’, Orbit (VSO’s International Quarterly), no.61, 1996, p.25. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid. 6 See Press Release, ‘National Ceramics Exhibition comes to Kaduna, Feb. 1st to 7th’. Joy Voisey’s papers, Cambridge, UK. 7 For a detailed account of the history of earliest ceramic art practice and education in Nigeria, see Ozioma Onuzulike, ‘The Emergence of Modern Ceramics in Nigeria: The Kenneth Murray Decade, 1929-39’, The Journal of Modern Craft, vol.6, no.3, November 2013, pp.293-314. 8 See E.H. Duckworth, ‘The Art of the Potter’, Nigeria Magazine, 1938. 9 For a view of the products of the Ibadan Pottery, see Tanya Harrod, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century, London: Yale University Press, 1999, p.191. For a full historical account and other pictorial illustrations, see ‘Pottery Manufacture in West Africa’. The Pottery Gazette, December 1, 1911, pp. 1346-1347. 10 See A. Hunt Cooke (Superintendent of Education, Southern Provinces). Letter to the Senior Resident, Oyo Province, Ibadan. In ‘Nigeria Minor Industries 1936-1951’. Oyo Prof. 2059. National Archives of Nigeria, Ibadan. 11 For one of Kenneth Murray’s published notes, see “A Kiln for Firing Clay Models”. Nigerian Teacher 2:6 (1936), 28-31. 12 For the catalogue of this exhibition, see Nigerian Wood-Carvings, Terracotta and Water Colours, London: The Zwemmer Gallery, 1937. For details of the press criticism of the exhibition, see Kenneth Murray, ‘The Exhibition of Wood-Carvings, Terracottas and Water-Colours, the Works of Five Nigerians Trained under the Nigerian Government, Held at the Zwemmer Gallery, London, 6th July to 7th August, 1937’, Nigerian Field, vol.7, no.1, January 1938, pp.12-15. 13 See Onuzulike, “The Emergence of Modern Ceramics in Nigeria…”. 14 For full archival information on the Pottery Training Centre, Okigwe, South-Eastern Nigeria, see ‘Local Industries’. OP. 1760 Vol. I ONDIST 12/1/1224. National Archives of Nigeria, Enugu. For photographs of some of the products of the Centre, see A.G. Saville, ‘The Okigwi Local Craft and Industries Exhibition’. Nigeria, no. 36, 1951, p. 453. 15 For full archival information on the Pottery Training Centre, Ado-Ekiti, South-Western Nigeria, see ‘Monthly Reports, Pottery Training Centre, Ado-Ekiti’. ONDO PROF 1/3 D.49. National Archives of Nigeria, Ibadan. 16 For elaborate historical analysis of Michael Cardew’s work in Nigeria, see Tanya Harrod, The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew, Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012. 17 For pictorial illustrations, see, for example, John Edgeler, Michael Cardew and Stoneware: Continuity and Change, (Winchcombe: Country Living Publications, 2008). 18 See Michael Cardew, A Pioneer Potter (London: William Collins, 1988). 19 Danlami Aliyu trained at the Abuja Pottery Centre from 1966 when he lived with Michael Obrien as a ‘house boy’ and later (in the late 1970s) with Cardew at Wenford Bridge before taking a Diploma at Farnham by OBrien’s arrangement. Danlami had written a thesis that reviewed the traditional pottery practice of Tatiko and the transformation that took place at Cardew’s Pottery Training Centre, Abuja. 20 See Pottery Quarterly: A Review of Crafts Pottery, vol. 13, no. 52, 1979. 21 This analysis derives from extensive personal conversations with Michael OBrien at his Addlertead Farm residence in Headly, Epson, during my research in the UK, October-December 2010. 22 Michael prefers to write his surname as OBrien instead of ‘O’Brien’. 23 Personal interview with Michel OBrien, Addlertead Farm, Headly, Epson, UK, November 2010. 24 Ibid. 25 Ibid. 26 Hamada was the famous Japanese potter who worked in England with Bernard Leach during the first quarter of the twentieth century. He used the Triaxial method in which glaze materials were practically tried out directly, at the end of which one is able to identify a workable recipe or blend. 27 Since the late 1980s, OBrien has continued with the mission of nurturing Cardew’s pottery project in Nigeria. He has taught the 'Hamada Method' almost like a creed both at the annual workshops of the potters and at the pottery village of Mararaba in Kaduna State, Northern Nigeria. He has sought to simplify the lessons in the form of cooking, which everyone can relate with, and he often does so in the Hausa language in which he is very fluent. 28 For a good insight into the Bwari Pottery and Michael OBrien’s role in the development of modern pottery in Nigeria, see Tolu L. Akinbogun, ‘Studio Pottery in Nigeria’, Ceramics Technical, no.22, 2006, pp. 91-5. 29 For insights into this pattern of pottery development in Nigeria, see Tolu Akinbogun, ‘Anglo-Nigeria Studio Pottery Culture: A Differential Factor in Studio Pottery Practice between Northern and Sourthern Nigeria’, The International Journal of the Arts in Society, vol.3, no.5, 2009, pp.87-97. 30 Personal interview with Joy Voisey, Cambridge, UK, November, 2010. 31 Ibid. 32 See Ceramic Voice newsletter, Issue 6, 1996. 33 For fuller information on the results of Ahuwan’s work with Mallam Idi, see Gloria Woyinkari Ikibah, ‘A Study of Abbas Ahuwan’s Hunkuyi Experiment’, Unpublished BA Thesis, Department of Fine Arts, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria, 2004. 34 For literature on this subject, see, for example, A.M. Ahuwan, ‘Trends in Contemporary Ceramics in Nigeria’, Environ: Journal of Environmental Studies, vol.1, nos. 2-3, November 1998-November 1999, pp.32-49; Emma Okunna, ‘Ceramic Art Practice in Nigeria: Fifty Years On’ in John Tokpabere Agberia (ed.), Design History in Nigeria, Abuja: National Gallery of Art, 2002, pp.55-9; Vincent Ali, ‘An Introduction to 20th Century Contemporary Nigerian Ceramics’ in Agberia, Design History in Nigeria, pp.60-70; and Moses O. Fowowe, ‘Changing Phases of Tradition: The Origin and Growth of Contemporary Pottery in Nigeria’, CPAN Journal of Ceramics, no.1, 2004, pp. 4-13. Top of the page | Download Word document | Next |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Making of National Ceramics Exhibitions of the Craft Potters Association of Nigeria (CPAN): An Historical and Critical Perspective • Issue 17 |